With the September 20 election less than three months away, and voters increasingly tuning into politics, we should expect to see a range of political advocacy groups promoting their causes. A particular target will be the 800,000 registered voters who failed to vote in 2011, since this voting bloc could affect the outcome of the election.

With the September 20 election less than three months away, and voters increasingly tuning into politics, we should expect to see a range of political advocacy groups promoting their causes. A particular target will be the 800,000 registered voters who failed to vote in 2011, since this voting bloc could affect the outcome of the election.

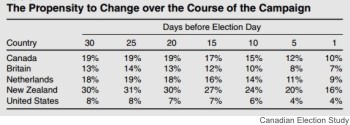

In 2002, a Canadian study on the impact of election campaigns on voting behaviour in five countries, showed New Zealand voters were more likely to change their minds in the run up to an election, than voters in Canada, the Netherlands, Britain, or the US. Almost one in three New Zealanders had not decided who to vote for a month before the election, with most only starting to firm up their voting intentions two weeks out from polling day. It was particularly revealing that some voters were still shifting from one choice to another by Election Day: about 4 percent in the US, 7 percent in Britain, 9 percent in the Netherlands, 10 percent in Canada, and 16 percent in New Zealand. These figures support the view that for some people their final voting decision is made at the very last minute.[1]

The 2011 Election Study by Professor Jack Vowles of Victoria University, confirmed these trends, finding that 35.6 percent of New Zealand voters had decided on their party vote “a long time ago”, 23 percent decided in election year but “before the election campaign”, 14.7 percent “during the campaign but before the last week”, 12.3 percent “in the last week before election day”, and 8.1 percent “on election day”. Some 3.4 percent “never did make up my mind” and 2.8 percent “don’t know”.[2]

In other words, with two thirds of New Zealanders making up their mind who to vote for in election year, and a third deciding during the campaign itself, the time is right for the appearance of hard-hitting initiatives designed to influence public opinion – such as the two new publications that were released last week on domestic violence and child poverty.

The People’s Report is the first tranche of Sir Owen Glenn’s $2 million inquiry into child abuse and domestic violence.[3] Set up in 2012, the final report of the inquiry is expected to be published before the end of the year as a policy Blueprint.

While there will undoubtedly be some worthwhile policy suggestions from the inquiry, this first report (which summarises the experiences of around 500 victims, offenders, and frontline workers) appears to have been largely captured by ideological interests.

Three examples will suffice.

Firstly, the study seems to suggest that colonisation is a cause of domestic violence. It states: “Māori were once a people who held in high esteem their tamariki (children) and wāhine (women) because of the treasured roles they had in their whānau, hapū (sub-tribe) and iwi (tribe). Nevertheless, colonisation brought with it new ways, including privileging the place of men, which rendered women and children as their possessions. As Aotearoa was settled, new ways of treating children and women were introduced to Māori whānau and hapū, which included beating them. Some, but not all, Māori chose to adopt these new ways in their whānau as they were pressured to become assimilated with colonialists.”

It goes on to say, the experience of colonisation is responsible for domestic violence, in that “these experiences broke down their wairua (spirit, soul) and their mana (status, control), making people feel whakamā (ashamed, embarrassed) and whakaiti (belittled) – some of which has survived in successive generations”.

While the Glenn inquiry suggests that colonisation is to blame for domestic violence and child abuse, Professor David Fergusson of Otago University, who heads the world renowned 25-year longitudinal Christchurch Health and Development Study, has found no such evidence.[4] Professor Fergusson’s Ethnic Identity and Intimate Partner Violence in a New Zealand Birth Cohort research, addresses this very issue, finding the extent to which the over-representation of Maori in domestic violence “is proposed by the systemic theory of colonisation… was not supported by the data”.

And that is the problem with the Glenn Inquiry. In choosing to use the experiences of people who have been involved in domestic violence as, seemingly, the sole arbiters of policy, the plausibility of the inquiry has been compromised.

A second example is their recommendation to shift in the burden of proof in domestic violence cases, so alleged offenders are considered guilty until they can prove their innocence. This is an idea that is so preposterous that it undermines the credibility of the whole report. The right of the accused to be considered innocent until proven guilty is a fundamental tenet of our legal system. It provides a crucial safeguard against wrongful conviction. That’s not to say that the court system shouldn’t be improved – of course it should. But allowing anyone to accuse someone of a crime – without having the evidence to back it up tested in a court of law – and then forcing the accused to have to fight to clear their name, is totally unacceptable.

While the report does acknowledge women are not only victims, but also the perpetrators of domestic violence – just as men are not only perpetrators but victims as well – those facts are not spelt out clearly enough.

According to the 2004-2011 Family Violence Death Review, prepared by the NZ Police, there were a total of 101 family violence deaths over that period, 37 adult females, 31 adult males and 33 children – 19 girls and 14 boys. 45 percent of the victims were male and 55 percent were female. Females killed 55 percent of the child victims, 32 percent of the adult male victims, and 8 percent of the adult women victims.[5]

Professor Fergusson’s research corroborated these figures, finding there was “No statistically significant main effects for gender, or gender-by-ethnicity interactions, suggesting that for both Intimate Partner Violence victimisation and perpetration, males and females reported similar levels of both victimisation and perpetration, and the results were similar for Māori and non-Māori females and males”.

The third example is that while the report acknowledges that children growing up in violent households are themselves at high risk of becoming part of the cycle of violence as adults, sufficient emphasis is not placed on the importance of family structure.

Traditionally, fathers played a vital role in bringing up and protecting their children. A father’s influence is crucial, especially for teenage boys. The former Principal Youth Court Judge, Andrew Becroft described the deep-seated need that boys have for a father figure: “14, 15, and 16 year-old boys seek out role models like ‘heat seeking missiles’. It’s either the leader of the Mongrel Mob or it’s a sports coach or it’s Dad. But an overwhelming majority of boys who I see in the Youth Court have lost contact with their father… What I’m saying is that I’m dealing in the Youth Court with boys for whom their Dad is simply not there, never has been, gone, vanished and disappeared”.[6]

The former Governor General, the Rt Hon. Sir Michael Hardie Boys, expressed it this way: “Fatherless families are more likely to give rise… to the risks of being abused, of being emotionally, even physically scarred, of dropping out of school, of becoming pregnant, of living on the streets, of being hooked on alcohol or drugs, of being caught up in gangs, in crime, of being unemployable, of having no ambition, no vision, no hope, at risk of handing down hopelessness to the next generation, at risk of suicide.”[7]

As the Ministry of Social Development report, The Scale and Nature of Family Violence in New Zealand: A Review and Evaluation of Knowledge shows, “While family violence affects families across the board, New Zealand studies show that the highest rates of partner abuse tend to be found among young, cohabiting adults of low socio-economic status, particularly when they have children”, with the “rates of abuse higher among cohabiters than daters or married couples”.[8]

What the study does not identify is that at the heart of these issues is the welfare system. The sole parent benefit in particular, by encouraging young women to raise families without a husband to protect and provide for them, puts the mother and her children into a position where they are at grave risk of violence and abuse. One can only hope that the Glenn Inquiry will focus on such issues in their future reports in order to address one of the main root causes of domestic violence.

The second publication launched last week was the book, Child Poverty in New Zealand, by Jonathan Boston and Simon Chapple. Dr Boston is a Professor of Public Policy at Victoria University and the co-chairman of the Children’s Commissioners’ Expert Advisory Group on child poverty. Simon Chapple is a Senior Research Fellow in Otago University’s Multi-disciplinary Health and Development Research Unit, having previously held positions with the Department of Labour, Ministry of Social Development, the NZ Institute of Economic Research, and the OECD.

Between them, these authors have extensive expertise, but at the launch of the book, Professor Boston likened the situation of poor children in New Zealand to that of children living in the slums of India. This is the same sort of exaggeration and extremism his Expert Advisory Group on child poverty has been using to claim that one in four New Zealand children live in poverty, and it seriously undermines confidence in his work.

This week’s NZCPR Guest Commentator, welfare researcher Lindsay Mitchell, has carefully read the book and shares her analysis with us. She refutes the claim that child poverty is the result of the benefit cuts in the nineties, demonstrating that supplementary assistance has risen at a faster rate than wages since that time. In particular she points out that increasing benefit levels would reduce the incentive to work.

“In my view, this is the crux of the matter. To maintain a margin between incomes from work and incomes from welfare, benefit payments should stay at their current level. However, greater efforts to get beneficiary parents into employment are paramount.

“It is particularly disappointing that the authors went back only to policies of the early 1990s to explain why child poverty increased so rapidly. I would take them back to 1973. After the domestic purposes benefit was introduced, the annual number of ‘unmarried births with no resident father’ grew from around 3,000 to reach around 12,000 by 1991. The numbers reliant on the DPB had rapidly grown to 97,000. With a relatively generous benefit payment available the employment rate for sole mothers plummeted over the same period. When the state could no longer afford the same level of generosity and cut benefits, child poverty soared. Nevertheless, it was, and remains, the change in family structure that drove up child poverty.”

Whether social policy advocates like it or not, the fact remains that sole parent benefits have done immeasurable damage to New Zealand society through breaking up families and exposing children to the significant risks associated with long term benefit dependency. The sooner the government undertakes proper reform of the welfare system to ensure that single parents are supported into work and self-reliance, the sooner family violence and child poverty rates will fall.

THIS WEEK’S POLL ASKS:

Do you believe ‘colonisation’ is an underlying cause of domestic violence and child abuse in New Zealand?

Click HERE to vote

Click HERE to see all NZCPR poll results

FOOTNOTES:

1. André Blais, How Many Voters Change Their Minds in the Month Preceding an Election?

2. Jack Vowles, Election Study 2011

3. The Glenn Inquiry, The People’s Report

4. Police, Family Violence Death Review

5. David Fergusson, Ethnic Identity and Intimate Partner Violence in a New Zealand Birth Cohort