Over the last few years, there has been a growing consensus amongst the leaders of western nations – including the UK, Germany, France, Spain, Holland, Belgium, and Australia – that policies and practices that divide citizens along ethnic and cultural lines are dangerous.

Over the last few years, there has been a growing consensus amongst the leaders of western nations – including the UK, Germany, France, Spain, Holland, Belgium, and Australia – that policies and practices that divide citizens along ethnic and cultural lines are dangerous.

In Holland, the Dutch government decided to abandon the long-standing model of multiculturalism that had created a parallel society within the Netherlands: “It is necessary because otherwise the society gradually grows apart and eventually no one feels at home anymore in the Netherlands.”1 In Britain, Prime Minister David Cameron went as far as calling for an end to government funding for organisations that promote separatism: “Let’s properly judge these organisations. Do they believe in equality of all before the law? Do they believe in democracy? Do they encourage integration or separatism? These are the sorts of questions we need to ask. Fail these tests and the presumption should be not to engage with such organisations”.2

The point is that while western leaders are busy condemning separatism, our government is assisting a march towards it. Over the next two weeks, two separate official events will show how far we have gone down the separatist path – they are the Census and the official launch of the Maori Party’s constitutional review.

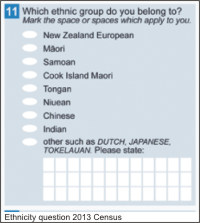

While the Census is normally regarded as being a benign enough event, when you drill down into some of the questions the divisions can be seen. Question 11 on ethnicity for example, sounds innocuous enough: “Which ethnic group do you belong to?” Eight options are given – New Zealand European, Maori, Samoan, Cook Island Maori, Tongan, Niuean, Chinese, and Indian. A ninth option “other” is also provided with space to write alternative ethnicities.

The problem is that ever since the ethnicity questions was changed in the 1980s from an objective measure based on the percentage of ancestry a person might have, to the modern-day subjective self-definition of heritage, the results have been interpreted in a way that dramatically overstates the number of people of Maori descent in New Zealand. In other words, if someone has a distant ancestor who was Maori, and ticks the Maori option as well as other options to reflect their more recent and dominant ancestry, all of those other ethnicities will be ignored and they will be classified by Statistics NZ as “Maori”. This practice grossly exaggerates the number of Maori in New Zealand with serious financial consequences, since these statistics are used as a basis for the allocation of resources for race-based Maori-only policies and funding.

Simon Chapple, a Senior Research Analyst with the Department of Labour outlined the implications of this in 2000, in a groundbreaking study, Maori Socio-Economic Disparity. Using data from the 1996 Census he explained, “In the 1996 census there were 273,693 New Zealanders who identified ethnically as Maori and Maori only. In addition to this, there were 250,338 New Zealanders who identified as members of another ethnic group, usually Pakeha/European, and also as Maori. Currently Statistics New Zealand’s official policy is to arbitrarily classify mixed ethnicity individuals who have Maori as one of their ethnic groups as Maori and not as the other group or groups to which they also belong. This sole plus mixed group is the Maori ethnic group as officially measured. In addition the 1996 census reveals another 56,343 New Zealanders with Maori ancestry but who do not identify ethnically as Maori. Adding these ancestry-but-not ethnicity people gives around 580,374 Maori in 1996.”3

He suggested that a more accurate reflection of the real situation could be obtained by retaining half of those classified as Maori as part of the Maori ethnic group, with the rest allocated to a non-Maori group using their other primary stated ethnicity.

Doing this same analysis for the 2006 census figures shows that of the 565,329 people classified by Statistics NZ as Maori, over a half (53 percent) identified with another ethnic group as well. Removing these people with multiple ethnicities leaves 265,704 who identified as Maori-only.4 This number is almost 8,000 less than the equivalent count in 1996, showing that those who identify as Maori-only in New Zealand are – as expected – on the decline. In 2006, people of Maori-only ethnicity represented 6.3 percent of the population – a considerable distance from the 14.6 percent officially claimed as the size of the Maori ethnic group that year.

The reality is that due to the rapid rate of intermarriage in New Zealand the boundaries of Maori ethnicity are blurring to such an extent that accurate ethnic categorisation has become almost impossible. As Simon Chapple explains, “Influenced by a bi-culturalism that views Maori and non-Maori populations as if they ran on separate parallel train tracks, the current conventional wisdom ignores the implications of intermarriage”. Yet he finds that the statistics in 1996 are far from immaterial – the partners of 7 out of 10 of the younger married and de-facto Maori ethnic group are non-Maori, and over half of Maori children now have a non-Maori parent. This means that claims that Maori are a distinct and growing population is a fiction – a political construct aimed at fulfilling elite tribal ambitions for money, power and resources.

With the world of Maori statistics and Maori funding totally politicised and lacking rigour, information based on this data should not be regarded as a true representation of the reality within New Zealand society. Why this situation has been allowed to continue is a serious question that deserves a serious answer.

In 1986, the year the ethnicity question was changed on the census form, 20,313 people objected by ticking the “other” box and writing “New Zealander”. In 1991, 20,800 did so, and in 1996, the number jumped to 58,614. By 2001, it had increased to 85,300, and at the last census in 2006, 429,429 people called themselves a “New Zealander”.

With ethnicity defined by Statistics NZ as “cultural identity based around commonly held values and beliefs”, it could be said that if 161 years after the New Zealand Constitution Act granted self-government to our Colony, we haven’t developed a unique New Zealand culture with common values and beliefs that would enable us to call ourselves “New Zealanders”, then there is something seriously wrong. Of course we have – it’s just that there are strong vested interests that do not want this ethnicity question to be changed.

In the end it may be that public pressure is the only way to get some honesty into our statistics. If that is the case, then here’s hoping that everyone who understands what’s going on ticks the “other” box and writes “New Zealander”. Census, authorities have admitted they are bracing themselves for even more people to take a stand against ethnic categorisation – maybe this time the numbers will force proper reform.

The other divisive official event is this week’s launch of the Maori Party’s Constitutional Advisory Panel’s “engagement” process. With its pre-determined objective of bringing the Treaty of Waitangi into a new written constitution as supreme law, a panel hand-picked to recommend this to the government, and a biased consultation process that puts special emphasis on Maori representation, this signals the beginning of a very divisive chapter in New Zealand’s race relations.

This week’s NZCPR Guest Commentator Professor Elizabeth Rata, a member of our Independent Constitutional Review Panel, explains how she was invited by the government panel to share her views. In her article How should we engage with our government, Professor Rata outlines the concerns she has about the whole government review process, and in response to the question of why New Zealanders should participate in the constitutional review process, she states:

“Because retribalists and biculturalists are campaigning to have the Treaty included in a constitution. This must not happen if we are to remain a democratic nation. New Zealanders must stop the inclusion of the Treaty in our Constitution. I belong to a Group, the Independent Constitutional Review Panel that includes members from across the political spectrum. We are currently promoting the ‘Declaration of Equality’ to oppose the Government’s Constitutional Advisory Panel. 38,000 New Zealanders have already signed the Declaration. We regard the Government’s Advisory Panel as compromised by Treaty politics. Its 50/50 race-based membership makes that clear. Our concern is that the Government Panel has the funding and resources to promote its agenda for the inclusion of the Treaty in a constitution. A group such as ours has few resources in comparison.” Professor Rata’s full submission can be read HERE (- we are pleased to report that almost 41,000 people have now signed the Declaration of Equality).

Any proposed change to a country’s constitution is a very serious matter. But with half of the $4.1 million in funding for the government’s review earmarked specifically for consultation with Maori, the outcome of their process will be heavily weighted in favour of the powerful iwi elite and other radical supremacists. Their ambition is a Treaty-based constitution, with an iwi-based ruling class co-governing New Zealand.

Since New Zealanders will not get a fair hearing – nor fair representation – through the government’s consultation and review process, the Independent Constitutional Advisory Panel has set up a submission process of our own. We are now inviting public submissions for the “People’s Review”. We are committed to representing the views of the wider public fairly and in an unbiased manner to the government later this year.

With regards to the submission process, it is important to remember that many of the items in the Terms of Reference are essentially distractions from the Maori Party’s sole purpose – entrenching the Maori seats and enshrining the Treaty of Waitangi into a new written constitution as supreme law. Accordingly, it is these matters that should be the major focus for all submitters in the review, since they have the potential to seriously divide New Zealand society in the future.

The terms of reference for the constitutional review include the size of Parliament, the length of the term of Parliament and whether or not the term should be fixed, the size and number of electorates, including changing the method for calculating size; electoral integrity legislation; Maori representation including the Maori Electoral Option, Maori electoral participation, the Maori seats in Parliament and local government; the role of the Treaty of Waitangi within our constitutional arrangements; Bill of Rights issues including property rights and entrenchment; and a written constitution.

A simple guide we have prepared on these matters can be found HERE.

If you would like to make a submission in the People’s Review, please visit the www.ConstitutionalReview.org website and follow the “Make an on-line submission” link. Submissions close in September and will be presented to the government in the Independent Constitutional Advisory Panel’s report later this year.

- The EU Times, The Netherlands to abandon multiculturalism ↩

- David Cameron, State multiculturalism has failed ↩

- Simon Chapple, Maori socio-economic disparity ↩

- Stats NZ, Quick Stats about Maori 2006 ↩