The admission that the Dunedin City Council is facing significant and long-term cost blow-outs over their new $230 million covered stadium should serve as a stark reminder that in local government bigger is not always better.

The admission that the Dunedin City Council is facing significant and long-term cost blow-outs over their new $230 million covered stadium should serve as a stark reminder that in local government bigger is not always better.

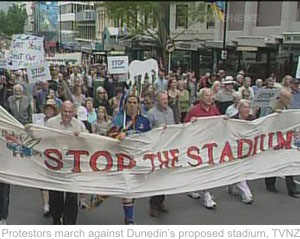

Unfortunately for Dunedin ratepayers, while the voices of caution over the stadium were many and loud, those councillors who were more interested in building legacies were resolute and ratepayers were forced to fund a project that many knew was going to be unsustainable.

This failure of elected representatives to heed warnings and take a more cautious approach, marks a fundamental failure of local body governance. Without more robust oversight and the necessary expertise to undertake ventures of such a large scale, residents and ratepayers should have been asked for their approval.

When concerned citizens called for a referendum to be held on the stadium, the council rejected the proposal on the basis that the public had already been consulted on the project through the 2008-09 annual plan process!

Mandatory referenda should be introduced as standard local body policy and practice. Councils should be required to send out an annual referendum questionnaire, along with background information and cost benefit analyses, to ask residents and ratepayers to prioritise and approve annual budget items – as well as decide the fate of highly controversial projects. Only this would ensure that those who foot the bill are well-informed and play a proactive role in the decision-making process.

Mandatory referenda should also be used to decide on amalgamation proposals.

Proponents of amalgamation claim that the consolidation of smaller councils leads to considerable cost savings and improvements in service delivery. Opponents cite the failure of central planning, and the fact that democracy and accountability are strengthened when small local councils are governed by local citizens and managed by local staff.

A 2005 report by Professor Paul Rouse of Auckland University, Local Government Amalgamation Policy: a Highway Maintenance Evaluation, which looked at the question of whether amalgamation improved local body performance found, there was “no evidence that amalgamation was justified in terms of diseconomies arising from smallness (i.e. increasing returns to scale). While new governance practices introduced contemporaneously lifted the level of performance of local authorities in terms of higher technical efficiency, there is no evidence that the amalgamation policy contributed to this improvement.”[1]

The paper points out that the United Nations strongly advocates amalgamation and larger units of local government. The evidence however, suggests larger councils are associated with higher spending, whereas the increased levels of public scrutiny and personal accountability of elected representatives in smaller councils, leads to lower levels of overall spending.

Historically, as a result of our geography and sparse population, New Zealand experienced a proliferation of local authorities – in 1912, with a total population of just 1 million, the country had almost 4,000 territorial and ad hoc local authority bodies. By 1989, these had converged into 700 councils and special purpose boards, which the Labour Government amalgamated into 86 local authorities. Today there are 78 local authorities – 11 regional councils and 67 territorial authorities, comprising district councils, city councils, and unitary authorities. Local government has become a significant sector of our economy making up 4 percent of GDP. Councils spend $7.5 billion per year of public money and manage $100 billion worth of public assets.

Not all countries believe bigger is better in local government. France has developed economies of scale for infrastructure such as roads and water (five water companies manage supplies for the whole of France), but not for local government. There are around 130,000 local bodies and a Mayor for every 300 or so residents.

In Switzerland, one of the most successful economies in the world, where great emphasis is placed on both efficiency and democracy, the average Swiss Commune (district council) has two thousand residents.

In some areas where amalgamation has been forced upon residents, they have rebelled and the amalgamation has had to be reversed. Probably the best known case is Montreal, which de-merged into 15 municipalities in 2006, just four years after amalgamation. The cost of the whole abortive affair was massive.

While National’s 2012 Local Government Act reforms introduced some positive changes, such as requiring councils to focus on their core business of providing infrastructure and essential services – as well as improving their prudential management – many felt that giving vested interest groups the power to bulldoze through amalgamation proposals was a backwards step.

Although it appears to be trendy to call for amalgamation styled on the new Auckland Council, many disillusioned Auckland ratepayers would not agree that theirs is a model worth replicating. Especially as Auckland’s local body amalgamation was borne out of political expediency, not good governance.

In 2006, there was fury over local body rate rises in the Auckland region. Rates, which had increased by 9.5 percent in the three years from 1999 to 2002, rose by a massive 25 percent between 2003 and 2006. The main driver was Labour’s 2002 Local Government Amendment Act, which had given councils the power of general competence and the mandate to consider the social, economic, environmental and cultural ‘well-being’ of their communities. As a result, many councils took their eye off their core responsibilities to engage in a plethora of activities such as buying farms in Australia, running multi-million dollar sporting events, or attempting to cure poverty.

The resulting lack of focus by many Auckland councils on increasing the supply of land for housing – to meet the needs of a rapidly growing population – was responsible for shortages that forced up property values and rates. In some areas, like Waiheke Island, valuations went through the roof, with one family, who had owned their property since 1836 reporting a 900 percent increase in their property valuation pushing their rates from $3,000 a year up to $16,000!

Faced with angry voters in the country’s largest city, Labour Party strategists, well versed in Politics 101, came up with amalgamation as the answer! They appointed a Royal Commission (which included a former Labour Party candidate) and the amalgamation process was launched.

The timing of the review meant it was the National government that received the Royal Commission’s report and made the decision to proceed with Auckland’s amalgamation. With the Maori Party as part of the governing coalition, there was pressure to establish Maori seats on the new council. But with the Minister, Rodney Hide, strongly opposed to Maori seats, an Independent Maori Statutory Board was established instead. Costing over $3 million a year to run, the nine un-elected Maori representatives on the Board have voting rights on council committees, often holding the balance of power.

These days, with the Auckland Mayor engulfed in scandal and the council only limping along, it is difficult to assess the true impact of Auckland’s amalgamation experiment. It’s therefore a major concern to find that the Local Government Commission is using the Auckland Council as a model for other regions and imposing Independent Maori Statutory Boards.

This week’s NZCPR Guest Commentator is Michael Coote, an Auckland-based freelance writer and financial journalist who closely follows Auckland council developments:

“Auckland’s unfortunate political experiment in having an Independent Maori Statutory Board is being held up as a model for the rest of New Zealand’s fragmented local bodies considering amalgamation into unitary authorities.

“The principal qualification for belonging to the Key-Sharples affront to elective democracy the Independent Maori Statutory Board represents is that board members must be part-Maori, with claims to being either mana whenua (Auckland tribal) or mataawaka (non-Auckland tribal). The nine-member Board has turned out to be a ratepayer-funded junket. These exclusively privileged individuals are unique in being officially permitted to vote on Auckland Council subcommittees as of racial right without democratic franchise from the wider community of residents and ratepayers.

“Disturbingly, the Local Government Commission, a permanent commission of inquiry, is trying to dupe residents and ratepayers of other local authorities seeking amalgamation into having an Independent Maori Statutory Board lookalike of their very own.”

The two amalgamation proposals that are presently being considered by the Local Government Commission relate to Northland and the Hawke’s Bay. Submissions for Northland’s proposal close on 21 February and can be made HERE, and submissions for the Hawke’s Bay proposal close on 7 March and can be made HERE.

In the Northland case, iwi leaders supported the former Far North Mayor in his bid to replace the Far North District Council and the Northland Regional Council with a Unitary Authority. In return for their support they were promised a third of the seats on the new council. It seemed like a cosy arrangement – the Mayor would get a share of the Northland Regional Council’s $120 million investment portfolio, and unelected iwi would get to occupy a third of all the council seats.

Their deal led to the Local Government Commission proposing the reorganisation of the whole Northland region with one Northland Council, as a unitary authority, replacing the four existing councils – the Far North, Whangarei, and Kaipara district councils and the regional council. There would be one mayor elected at large, with nine councillors, and seven community boards with 42 elected members.

Two new bodies would also be created – especially for Maori: an independent Maori Statutory Board made up of councillors and representatives from all 13 local iwi, and a Maori Advisory Committee to advise the council committee on Resource Management Act issues.

The Hawke’s Bay proposal follows a similar pattern – a single unitary Hawke’s Bay Council to replace the region’s five local authorities: the Napier, Hastings, Wairoa, and Central Hawke’s Bay councils and the regional council. The new council would be run by a mayor and nine councillors. There would be five community boards with 39 elected members, a Maori Statutory Board made up of the council and representatives of the ten local iwi, and a separate Maori committee to deal with the management of natural resources – for more details, see Mike Butler’s excellent blog Bigger councils not always better.

Once the consultation process is over, if the Local Government Commission remains convinced that amalgamation has widespread support and should go ahead, the proposal can be overturned by the public if 10 percent of affected electors demand a poll within 60 days. A region-wide referendum would then be held to decide whether the amalgamation should proceed.

This new system that National has introduced means that residents, who are very happy with the performance of their local councils, can now be bulldozed into amalgamation by vested interest lobby groups. As it stood, amalgamations could only be proposed by a consensus of councils or electors – or by the Minister. Furthermore, it could only proceed if a majority of electors in each affected area voted for change. Dropping that safeguard of requiring majority support in each of the affected areas in favour of a simple majority of the votes cast overall, is an affront to the democratic rights of residents and ratepayers and should be changed.

The NZCPR has established a number of Working Groups – including one dealing with local government reform – and we are inviting readers, who are interested in helping to shape policy and influence the debate, to visit our website HERE and register.

THIS WEEK’S POLL ASKS:

In principle, are you in favour or opposed to local body amalgamation?

Click HERE to vote

Click HERE to see all NZCPR poll results

Footnotes:

1. Paul Rouse, Local government amalgamation policy: A highway maintenance evaluation