A huge amount is said about child poverty, but bugger all about what causes it.

By the end of last year 13, 634 of the babies born in the previous 12 months had a parent or caregiver relying on a benefit. Data supplied under the Official information Act reveals that 48 percent of these caregivers were Maori. Assuming the ethnicity of dependent children generally matches the ethnicity of their caregivers, 37 percent of all Maori children born in 2011 were on welfare by the end of the same year. The corresponding figure for non-Maori was less than half at 16 percent.

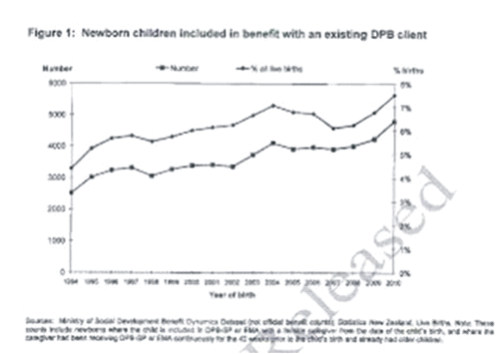

Most of these babies are born directly onto a benefit – usually the domestic purposes benefit. Some are first births. It’s not unusual for their mothers to initially be dependent on either the sickness benefit for pregnancy or the dole, then transfer to the DPB with the newborn in tow. But according to a Cabinet Paper publicly released last year, in 2010 4,800 births were second (or subsequent) children being added to an existing DPB. This happens most commonly in Whangarei, Whakatane, Rotorua, Kawerau and Wairoa, and the rate at which children are added has also been increasing.

The high rate of NZ children born onto welfare gives rise to numerous health and social problems down the line, not least abuse and neglect. We now know thanks to a recent Auckland University study that 83 percent of substantiated child abuse and neglect cases concern children who appear in the benefit system before the age of two.

There is an especial problem with Maori children. Not only are they more likely to be born onto a benefit, but they are more likely to have a very young mother who will have difficulty raising her child away from the sort of environmental risks that result in teenage parenthood in the first place; a dysfunctional family life, alcohol and drug abuse, family violence, transience, and crime. A strong correlation exists between the over-representation of Maori children on welfare and their marked predominance in many other negative statistics surrounding poor health and low educational achievement. Being born onto a benefit does not set them up for life.

Some of these children are going to be a cost to society for their entire lives. There isn’t any equivalent NZ research but American studies into the backgrounds of prison inmates find many had very young mothers, were raised on welfare, or in foster care or other state institutions. That the NZ prison population is half Maori is almost certainly associated with the very high Maori rate of teenage birth; almost four times higher than non-Maori. Sadly, it isn’t just the first-born children whose lives are affected, but those who follow as well.

Back in 2006 New Zealand Medical Association deputy chairman Don Simmers told a conference that too many women were contemplating pregnancy on a benefit. It’s taken a long time – too long – but the government has now officially recognised the problem.

Minister for Social Development Paula Bennett believes that work has both social and economic benefits for parents and their children. Last month new rules were introduced to require people on the DPB with a youngest child aged 5 or older to look for and be available for part-time work. The Minister understands however that some mothers will try to avoid this new rule by having another baby. As a consequence, she says, “Sole parents who have another child while on a benefit will be exempt for [only] one year, in line with parental leave, before work obligations resume.”

Unfortunately, this measure alone leaves loopholes. Cabinet illustrates the lengths some will go to when identifying children, “who are moved between households to avoid work expectations.” There is currently no rule that prevents a parent from going off the benefit for a short period, having another baby, and returning with the clock starting afresh. This situation could have been avoided by adopting the US approach which simply time-limits the benefit. Federal law permits a maximum of 60 months over a lifetime of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (though individual states can deviate using their own funds). That regime unequivocally puts the responsibility firmly on the parent to limit their family size without totally dumping a safety net.

The other unthinkable work-dodge would be to produce a child annually. Ironically this outcome would be the exact opposite of what the government is trying to achieve. Again time-limiting the amount of welfare available would remove any incentive to go down this track.

Some favour capping the amount of money available to subsequent children born onto a benefit. Paula Rebstock’s Welfare Working Group considered this option but was persuaded by the Ministry of Social Development that adverse affects on the child or children might outweigh any favourable effect on child-bearing patterns amongst beneficiaries.

Beneficiary advocates have reacted to Paula Bennett’s new rule with hostility. Auckland Action Against Poverty spokesperson Sue Bradford says, “We believe that women in this country have the right to control their own reproduction.” This encapsulates the conflict between the so-called rights of women and the rights of children. Knowingly bringing a child into the world with no ability to raise him independently or adequately is hard to justify at any level.

The Norm Kirk government of 1973 which bowed to pressure to provide statutory assistance for mothers who’d lost the support of a partner, would have been aghast if afforded a glimpse of a future in which supposedly single woman were allowed, and even encouraged by some, to breed on a benefit. Twenty two percent of all babies born in 2011 were on welfare by Xmas. But even pre-recession, when NZ briefly enjoyed the lowest unemployment rate in the world during 2007, the percentage only dropped to eighteen. Having babies on a benefit is part of the NZ culture. That’s what’s primarily driving this country’s child poverty scandal. In a word, irresponsibility; irresponsibility of the people who produce the kids, but arguably worse, irresponsibility of the society that sanctions it.