The turnout in the 2011 election was 74 percent, the lowest for more than a century. Almost a million registered electors didn’t bother to vote. According to Statistics NZ, the most common reasons given for not voting were that they “didn’t get round to it, forgot, or weren’t interested”. Around 7 percent didn’t vote because they felt their vote “wouldn’t make a difference”.[1]

The turnout in the 2011 election was 74 percent, the lowest for more than a century. Almost a million registered electors didn’t bother to vote. According to Statistics NZ, the most common reasons given for not voting were that they “didn’t get round to it, forgot, or weren’t interested”. Around 7 percent didn’t vote because they felt their vote “wouldn’t make a difference”.[1]

While age, income, and migrant status also affected voting behaviour, with turnout lower for those who are younger, on a lower income, or are new arrivals – it is disillusioned voters who are being highlighted as a key reason that citizens’ initiated referenda should be binding.

Binding citizens’ referenda have long been regarded as a policy option in New Zealand that, it is said, will lead to greater public involvement in the law-making process. Advocates believe binding referenda will re-engage those who are disillusioned with the political process, sparking their interest and leading them to vote.

The concept of binding citizens’ referenda has been promoted by a number of parties contesting elections over the years, but this time around, it has been identified as a bottom line issue for one of the minor parties seeking Parliamentary representation and a say in government.

There is no doubt that the concept of citizens’ democracy is a powerful one. Abraham Lincoln’s inspirational vision of democracy as “government of the people, by the people, for the people”, evokes aspirations of a better and fairer society. It is, after all, the concept attributed with building Switzerland into a successful and prosperous nation.

But the question that advocates should be asking right now is whether the policy of binding referenda is feasible within New Zealand’s constitutional framework?

Every country that enables citizens to influence the law-making process through binding referenda has established those democratic rights through enshrining them in a written constitution. Since a written constitution is in fact a legal document safeguarded by the judiciary, this “higher” law protects citizen law-making from being ignored or overruled by the legislature.

However, New Zealand does not have a written constitution. Ours is a nation built on the common law and the sovereignty of Parliament. This means that as a representative democracy, we elect Parliamentarians to be our voice in government and we entrust them with the nation’s ultimate law-making power. Since under our system every Parliament is sovereign, even if a law was to be enacted to make referenda binding, a future Parliament would have the power to over-rule it.

This means that in order to introduce binding citizens’ initiated referenda, giving citizens the right to propose law changes or to veto new legislation once a threshold of support is obtained through a public petition, our fundamental constitutional arrangements would need to be changed.

Changing our constitutional arrangements to give citizens supreme power over Parliament is very similar in concept to the proposal the Maori Party brought to the table when they became National’s coalition partner in government in 2008 and 2011. They wanted to introduce the Treaty of Waitangi into a new constitution, with supreme power over Parliament.

In our system of democracy it is not possible however, for one or two parties in Parliament to implement major constitutional change on their own. Introducing a new written constitution for New Zealand is a change of such magnitude, that it would need the cooperation of all of the parties in Parliament, as well as the public.

In response to the Maori Party’s proposal to include the Treaty of Waitangi in a new constitution, the government launched a constitutional review to find out what New Zealanders thought of the idea. The three-year review of our constitutional arrangements produced very clear results: an overwhelming majority of New Zealanders do not want a new written constitution. They do not want unelected judges in charge of our country’s law-making process. They want to retain the sovereignty of Parliament and the flexibility our present unwritten constitution provides.

In fact, of the 5,259 submissions received by the Constitutional Advisory Panel, more than two-thirds were opposed to a written constitution. Just 28 percent were in favour.[2]

Advocates of binding referenda would no doubt argue that a new constitution is not needed, and that Parliament could simply pass a law to give citizens the power to challenge the government, through the safeguard of entrenchment, whereby a 75 percent super-majority vote would be needed if Parliament wanted to change it. However, to pass such an entrenchment law, a 75 percent vote in Parliament would also be needed, and it is highly doubtful that party support for binding citizens’ referenda is that widespread. Furthermore, entrenchment still does not ‘lock in’ a law change as any future Parliament that could muster a 75 percent vote, could repeal it.

Constitutional Law Expert, Professor Andrew Geddis of Otago University believes that adopting binding citizens’ referenda would represent “a fundamental change to the entire constitutional order of New Zealand. And fundamental constitutional changes shouldn’t be made by bare-majority governments on a straight party line vote. It’s constitutionally improper to even suggest that this happen – it would be like the Maori Party saying that their price for supporting a Government would be for that Government to legislate via a bare parliamentary majority to make the Treaty of Waitangi a ‘higher law’ constitutional document that could be used to strike down other laws. I don’t care whether you think that would be a good outcome; it would be a bad way to bring it about.”[3]

Professor Geddis explains, “the only way to make referendums ‘binding’ is to somehow make the enactment setting them up as a ‘higher law’ than ‘ordinary’ parliamentary enactments. Parliament would be legally unable to ignore a referendum outcome because the law establishing referendums places a limit on what all future Parliaments are able to do. But how can you do so? Only by re-jigging the entire constitutional order and, in effect, creating a written Constitution that the courts may enforce against Parliament. And you can’t do that by an ordinary Act of Parliament alone.”

In other words, the policy of binding citizens’ referenda, presents the country with a challenge of such magnitude that it is not at all clear whether an acceptable policy solution could be found.

This week’s NZCPR Guest Commentator is George Gair, a former Minister of Health and Mayor of the North Shore, who believes it would be a backward step for our democracy if Parliament allowed ‘activist’ groups to force binding referenda onto the country – “as they have done in the US state of California with disastrous results”. He explains:

“The trouble with referendums is they inevitably must focus on single or particular issues, or specific aspects of issues, and don’t, and can’t, in their ‘yes or no’ message, weigh the issues adequately in the wider context of society’s broad present welfare, or likely future needs.

“By contrast, when major political parties, either in government or opposition, advance significance policies, they must first find broad acceptance within their respective caucuses. In a well-run and well-led parliamentary team, the concept of caucus, and the team discipline which it provides, acts as an important brake, or at least a moderating influence, against the unwise and the impetuous.

“I am not suggesting referendums have no place, but I would like to feel that their use would be comparatively rare and be saved for important constitutional issues, and then only after lengthy debate and well informed public research and enquiry.

“When used in such circumstances involving constitutional issues, I believe, even then, they should require a major majority one way or the other to achieve acceptance. To ‘only be passed by a whisker’ is just not good enough.”

The point being made, that the Parliamentary process provides a moderating influence against the enacting of unwise legislation, is an important one. Apart from the relatively rare occasions where laws are passed under urgency, New Zealand’s Parliamentary process is a reasonably measured affair. When a Bill is drafted, the wide range of related and consequential matters that are affected whenever any law is changed, are considered as well. Best efforts are made by the politicians and the advisors involved in the drafting of the Bill to minimise any unintended consequences. Often considerable research and consultation will have been carried out in advance of the drafting process.

Once a Bill has been tabled in Parliament and had the First Reading debate, it is then referred to a Select Committee, where it undergoes public consultation. A controversial law change can attract many thousands of submissions, whereas non-controversial changes may attract few. Submitters are invited to present their evidence in person, if they wish, or by video link, if they or the Committee are unable to travel.

During the Select Committee process, Members of Parliament not only have an opportunity to cross examine submitters as they give their evidence, but they will often seek further expert advice to address the concerns raised by submitters. The committee’s recommendations will then be presented to Parliament, ready for scrutiny by the Committee of the House – a phase which enables amendments to the Bill to be introduced. This is followed by the Second and Third Reading debates, after which the amended Bill passes into law.

Under normal circumstances, the Parliamentary process is comprehensive. However, it can be rushed, with people who have taken the time to prepare a submission given only a minute or two to make their presentations to the Select Committee. In addition, opponents of a law change will often become extremely frustrated and disillusioned when the government does not listen to their arguments. In these cases, however, the problem is often not the Parliamentary process itself, but the fact that they are sitting on the opposite side of an ideological divide on that particular issue.

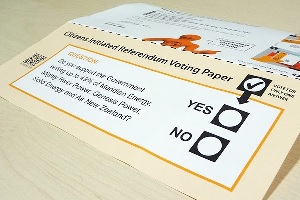

From time to time, opposition to an unpopular law change passed by the government gives rise to citizens’ initiated referendum, run under the 1993 Act. The problem is that because such referenda are not binding, if the referendum proposal is at odds with the government’s policy agenda, it will not be enacted. This of course leads to outrage and widespread public disillusionment with Parliament and the democratic process. But when it is all rendered down, the seeds of that disillusionment can be largely seen to be the referendum itself, with its implied promise to supporters that it would bring about change.

One of the main concerns raised about the concept of making citizens initiated referenda binding, is that the public can be too easily swayed by propaganda, and that there is no guarantee that a thorough informed process will underpin referendum voting.

Recent developments in this 2014 election campaign have elevated these concerns. The image of crowds of young people being worked up into a frenzy of hate against the country’s Prime Minister, highlights the manipulative and well resourced forces that are now present in New Zealand society. Ironically these well resourced forces are not coming from big business on the right, but radicals on the left. To expose the country to the threat of law-changes that could be forced through by people with extreme and selfish agendas is a very sobering reality.

Those promoting binding citizens’ initiated referenda might like to consider these issues very carefully before pushing for something that might turn out to be a far cry from the panacea they had hoped for.

THIS WEEK’S POLL ASKS:

Do you believe changing our constitutional arrangements to make citizens’ initiated referenda binding is in the best interest of the country?

Click HERE to see all NZCPR poll results

FOOTNOTES:

1. Stuff, Why people don’t vote

2. Mike Butler, Submissions reveal constitution panel’s trickery

3. Andrew Geddis, Colin Craig is asking for the impossible