Authored by Jonathon Boston and Simon Chapple, Child Poverty in New Zealand was published on June 18, 2014.

Two major reasons for child poverty are presented:

1/ Child poverty is a result of inadequate benefits which have eroded over time. In particular, the early 1990s benefit cuts increased child poverty rates and have never been restored.

The benefit value erosion explanation is troublesome though.

The authors refer to basic benefit rates as a percentage of average wages, claiming the sole parent rate had fallen to 27% by 2010. Yet elsewhere in the book they show the “sole parent benefit” as about $400 weekly[i] which was 48% of the average weekly income from wages or salaries in June 2013.[ii]

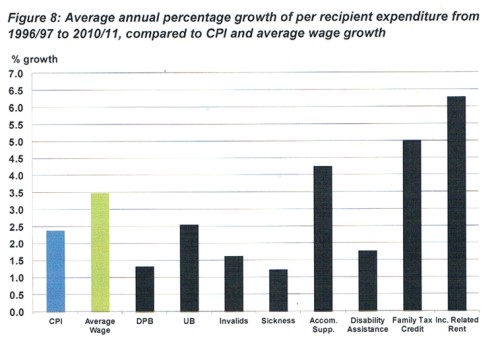

Additionally, supplemental assistance eg Family Tax Credits and Accommodation Supplement, have risen substantially and make up an increasing portion of benefit payments. In fact, along with Income Related Rents, between 1996 and 2011 they rose at a faster rate than wages. [iii]

Source: Working Age[Non-NZS] Welfare, Treasury, Figure 8

Today the Family Tax Credit for a beneficiary with one child is $92. In 1972 the Family Benefit was $3 (or $37 in 2014 $); in 1992 Family Support was $42 ($64 in 2014$). Additionally Accommodation Supplements range from $75 to $225 weekly according to residential area.

Late last year, according to Paula Bennett,[iv] an average payment received by a sole parent with two children living in South Auckland was $642 or 73% of the median income from wages or salaries in Auckland.[v] None of this is consistent with the ‘inadequacy of benefits’ argument.

The authors go on to claim, “…child poverty in New Zealand has been exacerbated in recent decades by high housing costs…” At Table 1.1 they allow accommodation costs for a sole parent with two children living in Auckland (high rent) of $360 which soaks up 55% of their benefit income.

Their policy solution to this is increasing the Accommodation Supplement in a targeted approach. However this risks driving up rents, especially if a compulsory rental accommodation ‘warrant of fitness’ and/or a capital gains tax are introduced, both endorsed in the book. The authors accept that this outcome cannot be ruled out.

In my view the most immediate solution to high accommodation costs is for sole parents to pool resources. The poverty rate for sole parents who live within a wider household is only 23 percent, close to that of two parent families. For the sole parent family living alone, the child poverty rate is 69%.[vi]

2/ Child poverty is the result of unemployment.

In one respect, this explanation is also problematic. When New Zealand had the lowest ‘official’ unemployment rate in the world – c.2007-08 – the child poverty rate persisted. This is because of New Zealand’s high rate of sole parent households (sole parent beneficiaries have not appeared in unemployment statistics until recently when those with children aged 14 and older transferred to the Jobseeker Support benefit).

One in 5 children will become benefit-dependent by the end of their birth year – usually a sole parent benefit. For Maori, the statistic rises to more than one in 3.

One in 5 children will be benefit-dependent for half of their first 14 years. That is the statistic driving the worst child poverty – the chronic, long-term hardship experienced during developmental years and it persists even when official unemployment is low. Some of this pattern, occurring since at least 1993, will be the result of unforeseen circumstances eg a redundancy. But generally the parent could have predicted their child’s ensuing reliance on income support.

Chapple (with good reason I assume he wrote the tax/benefit section) acknowledges that a sole parent in full-time work, and a two parent family with one full-time and one part-time worker, even at low wages, will earn enough to lift their children above most poverty thresholds.

To overcome long-term dependency, he recommends much stronger employment activation policies and work-testing sole parents at a much lower child age than is current practice. He draws on the Nordic states expectation that mothers will return to the workforce reasonably rapidly – when their child is 1 to 3 years old.

In the meantime though, a much higher level of assistance is recommended for young children. The authors want a universal Child Payment (to replace the complex existing range) which starts at a high level and reduces as the child ages. The economic rationale being that the real cost of raising children arises in the opportunity cost – ie the parent is least able to work when the child is a baby/toddler. They argue that countries which use universal approaches are more successful in reducing child poverty. Some means-testing is suggested, but not defined.

I have trouble accepting that the Nordic states approach will necessarily work in NZ however. Those countries have very low rates of teenage birth, more homogenous populations and a stronger work ethic. NZ on the other hand has a unique set of circumstances whereby Pacific and Maori women tend to parent young and more frequently. The latter rely heavily on the state to assist them financially. Typically, they have not acquired educational qualifications or work skills before they start their families so it isn’t a simple matter of returning them back to the workforce as quickly as possible. And, as I pointed out earlier, these are the families that will harbour chronic levels of child hardship.

Chapple’s advocacy of strong employment activation policies would require acquisition of educational qualifications/training post parenthood. Which begs the question, why weren’t first attempts to educate at secondary/tertiary level successful? And then, will second efforts be any more successful?

There is no discussion about the employability of many sole parents given either their lack of skills or experience. Worse, there is no attention given to the fact that many live in rural small towns like Kawerau, Ruatoria or Kaikohe, where employment opportunities are scarce and local businesses survive on social security incomes. This despite the author’s assertion that any strategy must, “… necessarily take into account the distinctive features of New Zealand’s cultural landscape … This includes issues of ethnicity and geography…”

Chapple is also quite clear that benefits reduce the incentive to work.

The payment of welfare benefits to families who do not work creates a number of potential issues. Firstly, as it guarantees an income to people not in paid employment, including those with children, it creates incentives not to work. While theoretically indisputable, much debate surrounds how large this effect is in practice, and how best to offset it.

Yet lifting child payments and accommodation subsidies would surely enlarge the effect. Having worked for the OECD Chapple will be aware that their own research has shown in English-speaking countries, reducing poverty via benefits increases the number of workless households. Writing about extending the In Work Tax Credit to beneficiary families Chapple says, “…such a reform would also reduce incentives for sole parents to find work, potentially raising the overall numbers of children in poor families.” In the same way, so would increasing benefit levels.

In my view, this is the crux of the matter.

To maintain a margin between incomes from work and incomes from welfare, benefit payments should stay at their current level. However, greater efforts to get beneficiary parents into employment are paramount. This could be achieved virtually expenditure- neutral. For example, by transferring benefit payments from Social Security into either Education or Health with a view to training more early childhood education or aged care workers. The possibilities for better spending are numerous.

It is particularly disappointing that the authors went back only to policies of the early 1990s to explain why child poverty increased so rapidly. I would take them back to 1973. After the domestic purposes benefit was introduced, the annual number of ‘unmarried births with no resident father’ grew from around 3,000 to reach around 12,000 by 1991. The numbers reliant on the DPB had rapidly grown to 97,000. With a relatively generous benefit payment available the employment rate for sole mothers plummeted over the same period. When the state could no longer afford the same level of generosity and cut benefits, child poverty soared.

Nevertheless, it was, and remains, the change in family structure that drove up child poverty.

Ironically, according to feminist Kay Goodger[vii], it was “A desire to prevent child poverty…” that led to the introduction of a well-paying benefit for single parents. Yet as she observed, “… as partnered mothers raised their levels of employment, sole mothers became increasingly separated from the mainstream. Disincentives in the benefit system contributed to this trend.”

The so-called cure for hardship and exclusion only exacerbated the problem.

If New Zealand was to return to higher benefit payments and the economy could not quickly produce enough jobs for the additional newly work-tested 60-70,000 sole parents, let alone the 122,000 existing jobseekers, we would only be digging a deeper dependency hole.

Employment for existing sole parents (and deterrence for prospective, particularly young, sole parents) is the current and most effective approach for reducing child poverty. In that respect the book is half right. But a strong and competitive economy capable of providing the required jobs won’t result from the greater taxation and wealth transfer the authors advocate.

Footnotes:

[i] New Zealand’s sole parent benefit is shown as US$17,711 annually, Table 6.1

[ii] The average weekly income from wages and salaries was $832. New Zealand Incomes Survey, June 2013, Statistics New Zealand

[iii] http://www.treasury.govt.nz/government/longterm/externalpanel/pdfs/ltfep-s3-03.pdf (p16)

[iv] http://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/better-work

[v] The median weekly earnings for people in paid employment in Auckland was $882. New Zealand Incomes Survey, June 2013, Statistics New Zealand

[vi] Revisions to Household Incomes Report, 27 February, 2014, Table H5, p 19

[vii]http://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/journals-and-magazines/social-policy-journal/spj10/spj10-maintaining-sole-parent-families.doc