When Social Finance launched the world’s first Social Impact Bond in 2010 our aim was modest, but our ambitions radical: we wanted to test the idea that it was possible to make positive social change investable. And we wanted to shine a light on a problem within our criminal justice system to make the case for more preventative, up front investment.

Five years on, we could not have imagined that the Social Impact Bond (SIB) and the ideas behind it would have resonated so widely. There are now 50 SIBs which have been launched and are in delivery, spanning 9 different countries, with many more projects and pilots under active development, including New Zealand where the Ministry of Health is in negotiations for a first SIB pilot.[1]

That original SIB, in the UK, was centred on male short-sentence offenders released from prison in Peterborough, a provincial town about 50 miles north of London. The problem we wanted to highlight was reoffending among this type of offender for whom, at that time in the UK, no statutory probation services were available. Budgetary choices have to be made by the public sector whatever the jurisdiction and, as it stood at that time, UK probation services were directed towards rehabilitation and post-release reintegration of offenders with longer sentences. With no systemic support for short-sentence prisoners, reoffending rates were high (over 60%), often with multiple previous convictions and periods of imprisonment. It was a recognised ‘problem’ in the system. Yet there was also some evidence that a well-thought through programme designed around an understanding of offenders’ needs had the potential to make headway in tackling their offending behaviour. And surely, if offending rates could be reduced, economic and social value would be generated, which would justify greater investment in prevention among this group?

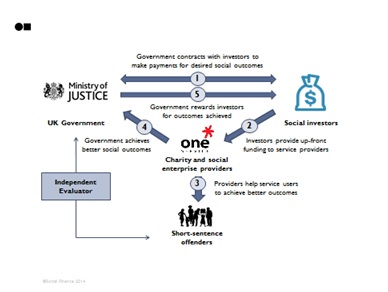

This was the genesis of the first SIB: the UK Ministry of Justice, the Big Lottery Fund, and the 17 social investors who placed their capital at risk were all motivated not only by the opportunity to tackle an acknowledged problem in a systemic way and at greater scale, but also to demonstrate the important societal value which might be generated by a collaborative, accountable model focused on the ultimate outcome of reducing reoffending rates.

Those investors committed £5m to fund a recidivism programme on the basis that, if the programme was successful in reducing reoffending rates by more than a pre-agreed amount (a reduction of 7.5% over the life of the programme), ‘outcome payers’ (the Ministry of Justice and the Big Lottery Fund) would reward that achievement under a ‘payment by results’ contract, which in turn would enable investors to be repaid. Correspondingly, a shortfall in performance would result in losses to the investors.

So what have we learned? Well – it’s hardly surprising to hear that our learnings have been profound, yet very practical. We’ve seen the need for staying power, persistence and the critical importance of building partnerships across all community and, in the case the Peterborough SIB, criminal justice stakeholders. Key elements of the Peterborough delivery model were to work ‘through the prison gate’, to identify client needs and be an effective bridge to community and statutory support. Many clients have chaotic lives and offending behaviour is both a product and a symptom of the issues they face: poverty, employability, homelessness, substance abuse, family detachment, mental health, etc. They are the ‘frequent flyers’ in the system who have disappointed – and been disappointed by – support agencies in the past. Why would this time be any different? Yet somehow, at the front line, it was: it is pleasing to hear, in independent evaluation, of clients’ positive experience of the One Service[2] and that the One Service was an improvement on their prior experience of post-release support.

In the process, we also acquired deep insight around the importance and value of tracking, comprehensively, activity and data rigourously and as near as damn it, in real time. Decisively, that data was not just collected, but used – to better inform an understanding of the needs of the client group and design of services. The focus on outcomes, with a flexible funding envelope, has led to an important body of knowledge which enabled us to focus more acutely on client needs and for the services to be adapted over the life of the programme. Progressively, the programme has become more fit for purpose as the performance management data has taught us where to focus efforts. The pilot project’s accountability was to outcomes, not activity, so we’ve also been able to try things out, and see how they can contribute to an improvement in reoffending behaviour: we’ve helped clients find new interests (fishing!), served jelly and ice-cream on family visits to encourage a more conducive environment, partnered with a construction company to develop a job training scheme. A new social enterprise which is helping ex-offenders to gain construction qualifications (and, more important, a job) will be a lasting legacy of the programme. We could never have done all these, and more, if the programme had been working to the traditional service specification model of contracting and activity based funding.

Peterborough was a defined term pilot, with service delivery recently coming to an end. We have results for the first cohort of 1000 ex-offenders among whom we saw a reduction of 8.4% in their frequency of offending. We will not know the full results of the entire programme until final measurement is completed by the independent assessor, though if the first cohort results are maintained or improved for the second cohort, investors will see a return on their investment. This final measurement will also determine the payment for outcomes to be made by the Government. Government has, though, already benefitted greatly: 2000 ex-offenders have received support which was not previously available to them, to date funded by investors.

The Peterborough SIB provides an interesting case study for attracting investment in prevention and as an accountability framework for investment in outcomes. And, as the SIB concept has travelled to other countries and to different social issue areas it has evolved, both as a model to pilot innovation and – for example, in the US – as a model which seeks to scale up investment in interventions which already have a strong evidence base behind them. Perhaps in the long term we shall see the power of the model is not the particular structure, more a set of principles around which to build effective cross-sector partnerships, with all partners aligned towards achieving specific social outcomes, and external investment capital bringing an additional level of accountability.

So, going back to the original ambition – did the programme succeed in shining a light on the problem? Reoffending rates among this group of offenders was an acknowledged problem, and there was also recognition of the potential to address it – but nonetheless, yes, by piloting a new way of financing prevention linked to outcomes, we do think it made a difference. Most obviously, a new, national, rehabilitation programme was introduced earlier this year – though a wider systemic change drove that reform, one key element is that the new programme will provide national coverage for this previously unsupported group of offenders in a systemic way for the first time.

SIBs (or, in the US, Pay-for-success Instruments) have now developed and/or launched in many other social issue areas. They are tackling problems such as adolescents at risk of going into care, social isolation among the elderly, and multiple SIBs have been commissioned in the UK and elsewhere which target employment and employability, in its different dimensions, among pockets of marginalized young people. The attributes to look for in these programmes reflect what we’re learning: rigour in the underlying analysis of the social problem; clear focus on outcomes; operational design; a flexible funding model; using the rigour of data to inform an adaptive learning approach to delivery. These are the principles that have shown the potential to drive change and, as SIBs are developed in New Zealand and other new jurisdictions, and on different social problems, these are the things to keep to the fore.

[1] http://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/preventative-health-wellness/social-bonds-new-zealand-pilot/social-bonds-progress-date

[2] ‘One Service’ is the operational name for the SIB project on the ground – signifying the single point of contact for the multiple services it brought together.