A very surprising Bill had its first reading in Parliament on 10 May. The Bill is surprising in that it was originally brought forward under the 2004 Foreshore and Seabed Act, which was abolished by the Marine & Coastal Area (MACA) Act in 2011.

The Bill, which was introduced into Parliament in September 2008 under the 2004 Act, gives effect to an agreement reached between the then Minister of Treaty Negotiations Michael Cullen and some of the tribal groups of the East Coast tribe Ngati Porou for their “territorial customary rights” claim. The next step in successfully gaining these rights was to prove their case in the High Court, namely that they had owned title to the land adjoining the claim, and had used the area continuously and exclusively since 1840.

However, after the November 2008 election, the National Government held a sham review of the Foreshore and Seabed Act and replaced with the MACA Act

This Ngati Porou Bill is the result of a deal between the former National Party Minister Chris Finlayson and representatives of the iwi, just before the 2017 General Election, to bring the agreement into line with the MACA Act.

However the Hon Andrew Little is now the Treaty Claims Minister, in the new Labour-led Coalition government, so is now responsible for this Bill. That he is continuing with Finlayson’s deal-making, by sending the Bill to a Select Committee, rather than reviewing what has been agreed, makes him look as if he is too much under the influence of Finlayson.

Little has also referred the Bill to the racially biased Maori Affairs Select Committee, rather than the Environmental Select Committee, as former PM Helen Clark did in 2004. This, and Little’s speech on introducing the Bill, shows him as very pro-Iwi, in his outlook, when one would expect a Treaty Negotiations Minister to be fair and balanced. This is especially the case, because Ngati Porou was never required to prove their customary rights in Court. Further, this Bill allows Ngati Porou hapu to put in a new claim under the MACA Act, even though the deadline for new claims has long passed.

It is important to understand that the MACA Act is not a Treaty Claim Act, although Labour has given responsibility for the Act to their Treaty Claims Minister Little. S 95 (4) requires that MACA claims must meet the requirements of S (58), a Customary Marine Title (CMT) or of S 51, a Protected Customary Right (PCR).

This requirement is quite different from Treaty Claims, which are decided by negotiations between the Treaty Claims Minister and the claimant tribal group. In the past Finlayson appears to have assumed that CMT claims by Ngati Pahauwera (Mohaka river mouth) and some hapu of Ngati Porou (East Coast) were wrongly considered as Treaty Claims. Labour has added to the confusion by naming their Treaty Claims Minister as in charge of MACA claims.

Let’s review the MACA Act, given that it expired for new claims on 3 April 2017 – over a year ago now. This was six years after the MACA Act came into force, (by Sections 95 (2), and S 100 (2)).of the MACA Act, and marks the cut-off date for new claims under that Act.

There are two customary rights which tribal group can gain – a Customary Marine Title (CMT), the strongest property right available to them, and Protected Customary Rights (see Subpart 2 – PCR including S 51 etc.).

It is CMT that is a major problem with the MACA Act, for outdoor recreational users, as it allows the setting up of wahi tapu areas, supposed sacred areas, of the foreshore and seabed, where only the tribal group’s members can go, and where the public, including other Maori, get fined up to $5,000 for every trespass. The Act also implies that wahi tapu should be established in good fishing areas. Tribal members may be authorised to police the area, as are fishery officers and voluntary fisheries officers. The public can only go there legally if there is an emergency e.g. a shipwreck. Hence wahi tapu stop recreational users recreating in areas, where they have recreated since 1840.

There are two paths by which a tribal group can qualify for CMT or protected customary rights. The first is via the High Court (S 98 and Part 2 Recognition by order of the High Court). The second path is by a “recognition agreement” where claimants negotiate the Crown, assisted by the Office of Treaty Settlements (OTS).

This direct negotiation with the Crown is called “Crown Engagement” (S 94 and S 95). It is solely at the discretion of the Crown as to whether it engages with the applicant (S 95 (3)).

Minister Andrew Little has said that his process for public engagement will be regional, but there will be no ability for the public to force claims to the High Court. Without this, his process will be a farce. The fact that deal-making with the former Minister was regarded as a ‘soft-touch’ can be seen from the fact that almost two-thirds of all claimants lodging claims by the 2017 deadline chose Crown Engagement.

It would be much better for Minister Little to refuse to negotiate most of these agreements, and have them go to through the independent High Court process (S 95 (3)). 50% of claimants have already hedged their bets by applying for both Crown Engagement and the High Court.

Claims under the MACA Act had to be filed before 3 April 2017. Prior to the deadline only about 40 tribal claims had been lodged, and a number of these had been challenged by the Crown as not meeting the conditions of the Act.

However, a tsunami of claims were filed on or around 3rd April 2017. Justice Department figures show that 202 claims are now lodged with the High Court claims and 385 claims for “Crown Engagement”.

This massive tsunami of claims at the last minute, seem to indicate, that tribal groups were trying to pull a fast one – had National and Finlayson remained in charge. There are now so many claims that they cover the coast two or three times over. Most claims overlap – yet it is not possible to have “exclusive occupation and use” when two claims overlap.

There is also massive conflicts of interest in dealing with the OTS, where desire to help tribal groups gain CMT etc is very strong. OTS administers Crown Engagement with the MACA Act and advises and helps claimant groups so they’re ready to enter negotiations.

Returning to the new Ngati Porou hapu Bill that is before the Maori Affairs Select Committee, the sole purpose of this Bill, as far as I can see, is to give the Ngati Porou hapu who previously subscribed to the cancelled 2004 Foreshore and Seabed Bill, a range of special rights over the foreshore and seabed in their tribal area, and two additional years to apply for CMT and (S 51) rights.

It is astounding that the Hon Andrew Little sees this as a valid process. The Bill should not proceed, and should not waste any more parliamentary time, since Ngati Porou’s claim was never proven in the High Court – a necessary condition for it to become legal under the Foreshore and Seabed Act 2004.

All former Minister Finlayson did was renegotiate their deal and gift them a range of special rights – it is up to Andrew Little to verify that their claims to the coast are valid.

We already know, from the cases in the Wellington High Court, that, it is very difficult for a tribal group to gain CMT on the New Zealand coast, as only one has succeeded – and was for a very small area of coast. CMT requires that various specific conditions be met, the hardest two of which are – (a) that the applicant has “exclusively used and occupied the claimed area from 1840 to the present day” and (b) that the application was made before the close-off date for tribal applications – six years after the Act came into force – namely by 3 April 2017.

In fact, this appears to be the real reason that this Ngati Porou Hapu Bill No 2 is needed, as the Ngati Porou hapu have neglected to register their claims before this date, in spite of over 200 other tribal groups having met this deadline. There has been a large amount of discussion and submissions about their claim, including disagreements with other tribal claims. Strong evidence exists that these hapu claims do not meet the exclusive occupation and use requirement – as discussed below.

There are very good reasons why it is very hard for any tribal group to gain a Customary Marine Title (CMT), especially around the East Coast.

Historic photos and maps show Stage Coaches driving along the beaches, in the sea, and on tracks around promontories, showing that the coast was the main path for walkers and coaches from 1840 until the Second World War. When steamships provided supplies and loaded cargo from the 1880s on, they loaded and unloaded across the foreshore, often to settler farms behind.

Photo 1: Landing passengers and cargo from coastal steamship, Waipiro Bay, East Coast 1890s, F R Hargreaves; Source: NZ Electronic Text Collection VUW Library.

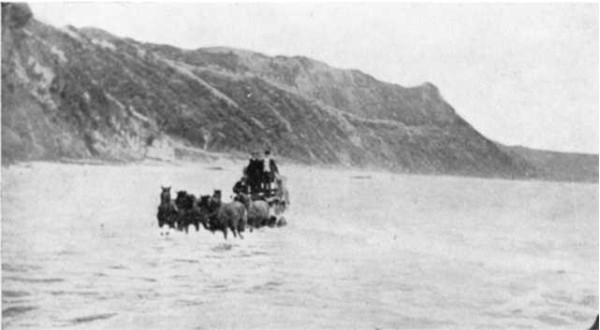

Photo 2: Royal Mail Coaches en route from Gisborne to Tolaga Bay, 1890’s; Source: NZ Electronic Text Collection VUW Library, Author Joseph Angus Mackay.

Photo 3: At sea. Off Tapuae Rocks. Treacherous section of old Gisborne-Tolaga Bay Coach Road; Source: NZ Electronic Text Collection VUW Library, Author Joseph Angus Mackay.

And from 1950s, better roads meant that people built baches along the coast, so ensuring that tribal groups did not generally have exclusive occupation and use from then on. The drift of Maori to the cities after World War 2 also reduced tribal numbers, often drastically.

As an outdoor recreationist, I have enjoyed walking the East Coast from Cape Runaway to Napier. At no time in my exploration have I been refused access to the foreshore and seabed, showing few if any areas of it are exclusively used and occupied by tribal groups.

The ownership of New Zealand’s foreshore and seabed was vested in the Crown under common law, in 1840, and has remained that way until 2011.

In general, the MACA Act has always been a very unfair and racist. Any tribal group gains massive free grants amounting to many hundreds of thousands of dollars from the Government to research and present its claim, while other parties opposing the claims have to pay registration, research and legal fees themselves. Thanks to Government policy, this means non commercial bodies such as my outdoor recreational association CORANZ – a broad-based volunteer national recreational advocacy group that is working hard to maintain free public access to the marine and coastal area for all New Zealanders, are at a serious disadvantage.

Submissions: I urge readers to make a brief submission on this Bill – HERE. Ask the Maori Affairs Select Committee why Ngati Porou hapu have been given the privilege of being allowed two additional years to claim Customary Marine Title. And ask who has tested whether Ngati Porou’s claims are valid, since they were never required to prove their case in the High Court, which was the requirement under the old legislation. Ask about what checks and balances there will be over the establishment of wahi tapu (so called “sacred” areas), where iwi members will have the right to charge anyone trespassing on what was formerly public land (the Crown-owned foreshore and seabed prior to 2011), where the tribal group can fish etc, but where members of the public – including other groups with a different Maori ancestor – all of whom have had the right to go there since 1840, will be fined up to $5,000 for every trespass.

This Bill has, as its main reason for existing, the desire of the Labour led Coalition Government to give Ngati Porou hapu the opportunity to obtain various MACA property rights, for two years after this Bill is passed. No other tribal group is getting this right. It is unfair and unjustified. What have Ngati Porou done to justify such special treatment? Nothing!

This Bill should not proceed. Please propose this in your submission. The Labour led Coalition Government should withdraw this Bill.

Dr Hugh Barr, Secretary, Council of Outdoor Recreation Associations of New Zealand (CORANZ).