Finance Minister Grant Robertson loves cricket; his Budget was that of an opening batsman.

It was defensive, clearly intended to cut off National’s initiatives before they got any real political oxygen.

Only occasionally did it show any signs of flash.

The law firm, Chapman Tripp, summed it up in their commentary. “Labour needs a circuit breaker to arrest its decline in the polls and allow it to regain control of the political narrative, and this was a job the budget might have done, but Finance Minister Grant Robertson was clearly more focused on restoring his credentials as a prudent fiscal manager after the Covid-19 splurge,” the firm said.

In his speech in the Budget debate, National Leader Christopher Luxon repeatedly talked about a “cost of living crisis” induced by the current inflationary forces.

Their answer is to raise the tax thresholds, which would see someone on the median wage ($56,160 a year) get an extra $800 in the hand. Robertson, instead, is proposing a “temporary” rebate of $27 a week for those earning less than $70,000.

It will apply for only three months which Robertson says will means each payout will be $350.

It is estimated to cost $814 million, and the Government is paying for it out of $3.2 billion of leftover funds in the Covid Response and Recovery Fund.

The current excise duty and road user charges cuts are to be extended for two months, and half-price public transport extended for another two months and made permanent Community Services Card holders from September.

There was also legislation introduced into Parliament to stop supermarkets from blocking their competitors from accessing land to open new stores.

In essence, all this was Robertson’s response to Luxon’s “cost of living crisis.”

But there was also some worrying data in the Budget documentation.

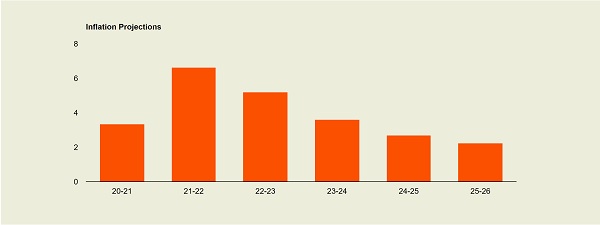

Treasury is forecasting inflation to gradually begin falling this year until it gets below three per cent (the Reserve Bank’s upper inflation limit) in 2024-25.

National Leader Christopher Luxon is focusing on inflation as the core of his attack on Robertson.

“The Budget forecasts that inflation isn’t actually due to come down below 3 per cent until 2025,” he said in the Budget debate.

“And what that actually means is that this cost-of-living crisis is going to go on for longer and for some time, and Kiwis will keep going backwards.”

The ANZ Bank’s senior economist, Miles Workman, described the inflation forecast as “frankly alarming” because Treasury was saying most of the inflation would be non-tradable inflation generated domestically.

“The concerning persistence in non-tradable inflation (bolstered by the tight labour market) means that an aggressive monetary policy response is needed, even if it will likely cause higher unemployment,” he said.

Kiwibank’s economists also see non-tradable inflation as a particular worry.

Jeremy Couchman, and Mary Jo Vergara, said: “Blocked supply chains, rising energy prices and elevated shipping costs have pushed prices higher. But a lack of spare capacity, particularly in the construction sector, has driven non-tradable (domestic) inflation higher, reaching a 30-year high of 6.6% in March. What’s worrying is that domestically generated inflation is the stickier, more persistent kind. Indeed, the Treasury sees non-tradable inflation essentially flat and above 6% until the latter half of 2023.”

Robertson conceded that inflation was the major challenge.

“Inflation is peaking across the advanced economies at the highest levels in decades,” he told the Budget media briefing.

“And yet, as central banks unwind stimulus and increase interest rates, there are concerns that the second half of the year could see recessions in some part of the parts of the world.

“It is a challenging and uncertain environment in which to be putting together a budget.”

Perhaps surprisingly, Treasury is projecting buoyant GDP growth for next year (4.2%) but is also forecasting that to fall back down in 2024 to 0.7 per cent; unemployment will also rise that year.

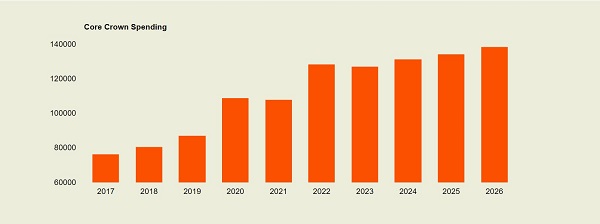

National is also attacking Labour over its spending projections.

“Grant Robertson has a problem, and his problem is that he is so deeply and utterly addicted to spending, and I want to say that the impact of his addiction on our fiscal books is incredibly clear, and when you think about it, he’s damaging New Zealand’s economy very strongly,” said Luxon in the Budget debate.

“This is—be under no doubt—a massive Budget blowout.

“This Government—and I want to just step it through—has increased Government spending since coming to power by 67 per cent.”

Robertson defended this year’s $5.9 billion increase as prompted by the need for spending on health reforms.

The big-ticket item is $1.2 billion to fund the DHB deficits. There is also a range of increased funding across the sector, including the biggest-ever increase for Pharmac ($71 million) with a projection of another additional $120 million next year.

The Pharmac funding is part of a new multi-year funding approach to health which will see that extended to a three-year cycle from Budget 2024.

In many ways, Robertson and Health Minister Andrew Little are having to fund years of underfunding in the health system.

Robertson used this chart in his presentation to show how the Key/English governments had not increased health spending to keep pace with population increases.

“The 20 DHBs have collectively run deficits in 12 of the 13 years since 2009, meaning that their annual spending was more than the government funding, leading them to eat into finances like money that had been set aside for hospital maintenance,” said Robertson.

“Deficits since 2009 totalled more than $3.5 billion.

“But the benefit of their spending has not been equally shared by communities across the country.”

Robertson’s political challenge with the health reforms is that there may not be much to show for them by the time of the election next year.

They are not a short-term circuit breaker.

Overall, Robertson was able to produce a Budget that showed an end within the foreseeable future to deficits and for borrowing to stay within the Government’s new debt limits.

Westpac’s economists concluded that the Government’s accounts were in good shape.

“While the operating balance isn’t expected to return to surplus for another three years, it’s on a credible path there, and the debt requirement looks manageable,” their economics team said.

“It’s all well in line with the new fiscal rules that the Government set out a few weeks ago, which allowed for more flexibility around spending while still providing some discipline.

“But it’s early days for the new framework.

“While this year’s Budget conforms with the new rules, it doesn’t necessarily guarantee that future Budgets will be. For example, the multi-year approach to funding allocations in areas such as Health, Natural Resources and Justice means that a large part of the new spending allowance for next year’s Budget has already been pre-allocated.

“That would imply that other departments’ funding demands will be squeezed into a tighter cap than otherwise.”

The Labour Party will not thank Robertson if they are still too close to National in the polls next Budget and he has no money to spend.

Prudence can have a price in politics.

This article was first published by Politik – see HERE – and is reproduced with the kind permission of the author.