Since the National government took office late 2008, welfare reform has formed a large legislative programme much of which has now been completed. It is perhaps too soon to expect benefit numbers to start reducing, complicated by the global financial crisis driving up unemployment in 2009-10. But we should nevertheless be interested in the latest headline numbers as well as, arguably more important, the duration of dependence.

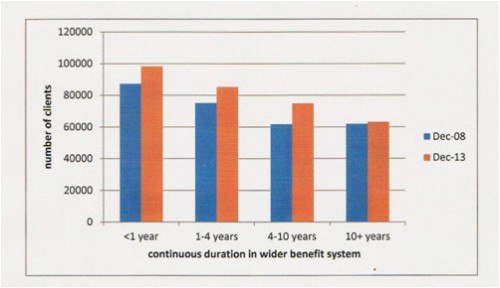

The Ministry of Social Development now only publishes time spent on benefit in two categories: under and over 1 year. To make comparisons to older data I requested a more detailed breakdown. In every duration band the numbers were higher at December 2013 than they were in December 2008.

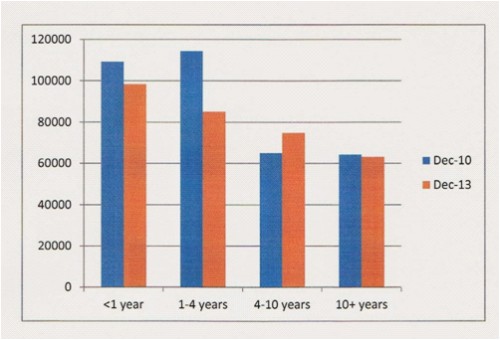

As mentioned though, the effect of the GFC must be taken into account. It peaked in 2010 so I have further compared December 2010 to December 2013.

As you’d expect, with gradually improving employment and possibly because of welfare reforms, the shorter term dependants decreased. But the 4-10 years number increased and the ten years plus number has barely budged. This is important because long-term dependence is detrimental to the health and well-being of individuals and their children, and the financial cost to the country is much higher than for short-term recipients.

If I use the National government’s official definition of long-term dependent – one year plus – the percentage has actually increased ever so slightly between 2010 and 2013 from 69 percent to 69.4 percent.

The government’s goal to reduce welfare dependency hasn’t been met in these terms, although there are signs that overall numbers are starting to reduce. The total has fallen from 353,000 in December 2010 to 322,000 in December 2013 (which is still higher than when they became government).

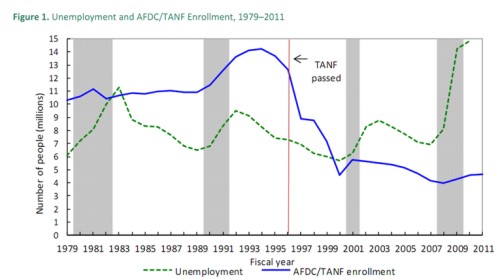

The only emphatic success in reducing beneficiary numbers that I am aware of in the developed world came after the introduction of time-limits in the United States. Under Bill Clinton the federal government made it illegal for states to use federal funds to support Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) clients for more than 60 months. Individual states could impose stricter limits if they wished or use their own public funds to extend limits.

In 2011 the Urban Institute looked at what role TANF was playing in the recession. They concluded that unemployment benefits (which are funded through payroll taxes) were absorbing much of the need.

“…three in ten low-income single parents received unemployment benefits in 2009, double the share receiving in 2005. This suggests that as more single mothers went to work during the late 1990s and early 2000s, more could qualify for unemployment benefits in the event of job loss. Also, many states have recently expanded eligibility for unemployment benefits.”

So while the recession was a bad news story for single parents, at least many had acquired job skills and experience they wouldn’t have if TANF time-limits hadn’t been introduced. Also, unemployment benefits in the US (based on previous employment earnings) are more generous than TANF. Hopefully these parents will return to the workforce as employment picks up.

The Urban Institute goes on to comment about the TANF numbers staying low despite the recession, “State TANF policies discourage welfare use: TANF benefits have remained flat over the past 15 years in most states, diminishing the value to low-income families. Maximum TANF cash benefits are less than 30 percent of the federal poverty threshold in 30 states (Zedlewski and Golden 2010). Also, many states actively discourage applicants from enrolling in TANF.”

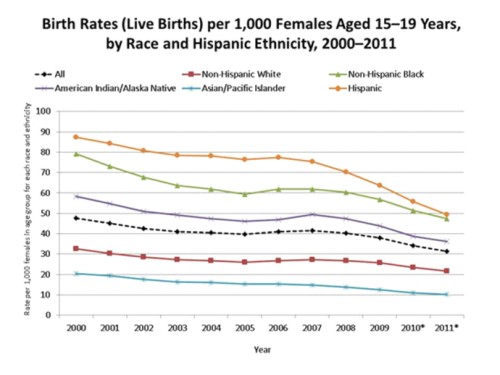

As well as requiring time-limits the federal government capped what they would pay for TANF which has slowly reduced its value. At the same time housing subsidies and food stamps are available to cushion the impact. But people are discouraged from getting into a situation where they need to apply for this type of assistance. This may well be one of the reasons the teenage birth rate is now falling. The following graph from the Centre for Disease Control, the official source for US birth data, highlights the greatest reduction amongst the poorest ethnic groups:

Time-limits send a strong and unambiguous message. So could they be applied in this country?

Putting them on the Supported Living Payment (ex invalid benefit) would be nonsensical given the debilitating and often chronic nature of incapacity these beneficiaries experience. Likewise their carers, often also a beneficiary.

But time-limits could be applied to the Jobseeker Support (ex unemployment benefit). In the US unemployment benefits are available for a set term. In a crisis these terms can be extended via legislation but these extensions are treated as exceptional. The pervasive thinking in the US is that unlimited assistance prolongs the period an individual spends unemployed.

They could also apply to the Sole Parent Support (ex DPB). Currently a single parent needs to be available for part-time work when her youngest turns 5 but that can involve very low hours plus benefit for a number of years. For someone returning to the system with a newborn, the clock starts again. That couldn’t happen under time-limits.

It would be entirely feasible to set a 36 to 60 month time limit across all but the Supported Living Payment. Making it a ‘lifetime’ limit also tends to encourage people back into employment or a supportive relationship as quickly as possible so they can save up entitlement for a later ‘rainy day’. Time-limits would introduce positive incentives.

And here’s an election year idea. To make time-limits even more attractive to voters, their introduction could accompany a lifting of ineligibility for unemployment assistance after a redundancy because, for example, the individual has a working partner. There is a case to be made that every individual who works and pays tax should have an unemployment benefit entitlement.

If the government is serious about reducing long-term benefit dependency more radical reform will be needed.