A recent Amnesty International report made the following observation about New Zealand:

The 2013 Technical report on Child Poverty found that 27% of New Zealand children remained in poverty. Maori and Pacific island children were disproportionately represented in child poverty statistics, highlighting systemic discrimination.

Really? Which system is discriminating against Maori andPacific Island children?

With free GP visits and prescriptions – recently extended to all under 13’s – it’s not the health system. With community service cards and medical centres like the Petone Union Health Centre which provides “comprehensive primary health services to Maori, Pacific, Refugee and low income families” free to patients 18 and under, the case could be made that Maori and Pacific Island children are the subject of positive discrimination though that is unlikely what Amnesty International intended. Immunisation rates are steadily increasing (PI rates are now higher than NZ European). School nurses are a feature in low decile schools and of course, whanau ora services are specifically aimed at improving the health of Maori families. Oral health services are free to all children and adolescents. Maternity services are targeted at low income vulnerable mothers-to-be dominated by Maori and Pacific Island females.

Is it the education system they refer to? The targeted funding to low decile schools is well-known. Charter schools are being established in some of the poorest neighbourhoods to meet the challenge of the under-achieving tail. Free hours of early childhood education have been steadily expanded. Again a case could be made for positive discrimination as opposed to negative.

Perhaps Amnesty International meant that the labour market discriminates against Maori and Pacific Island and, by proxy, their children. Yet it is unavoidable that low or no educational qualifications will predict future employability. Which takes us back to the education system that, as alluded to earlier, has, for the most recent decades, operated in a manner that exercises positive rather than negative discrimination towards ethnic minorities. Targeted funding of low income schools is synonymous with targeted funding of Maori and Pasifika.

Is the social assistance system stacked against them? Are Maori and Pacific Island children being denied benefits that NZ European children access? Again, the opposite is nearer the truth. Maori children, in particular, disproportionately receive social assistance, especially by way of Sole Parent Support.

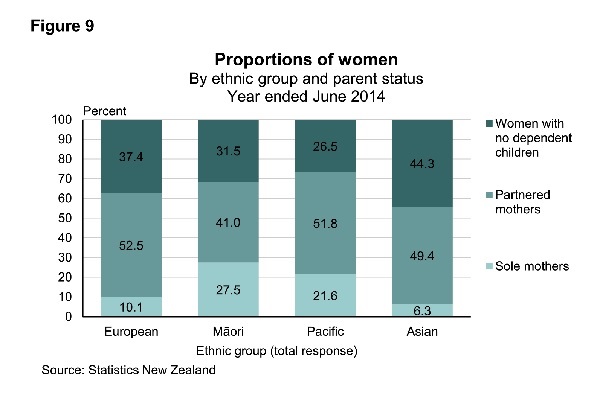

A recent New Zealand Statistics report into the employment rates of NZ females featured the following graph:

It reveals that 40 percent of Maori mothers, and 29 percent of Pacific Island mothers are unpartnered. This has a direct bearing on child poverty.

The official source of child poverty statistics is the Household Incomes Report published by the Ministry of Social Development. It finds:

…the poverty rate for children in sole-parent families living on their own is high at 60%…the poverty rate for children in two-parent families is much lower at 14%…

Is there some systemic discriminatory force that prevents Maori and Pacific Island parents from forming stable partnerships?

I don’t know what it is.

There is validity to the theory that welfare benefits have undermined marriage. If the state is prepared to financially replace fathers, especially low income fathers, then there will be inevitable repercussions. When the universal, non-means-tested family benefit – paid directly to mothers – was introduced in the 1940s, Maori marriage rates climbed. Only married mothers qualified to receive them.

In The New Zealand family from 1946, Treasury comments:

Legal marriage is now less common among Maori than among non-Maori …The estimates for people aged 60 and over are, however, an exception. Maori in this age group—who would have been entering the main marriage ages during the baby boom—appear to have just as high a probability of ever marrying as other New Zealanders of the same age. Maori in earlier periods had not seen any great need to ask non-Maori officials to provide legal sanction for their marriages (Pool 1991: 109) so the baby boom may well have been the high water mark for legal marriage among Maori.

After the 1973 Domestic Purposes Benefit (DPB) guaranteed eligibility to a relatively generous benefits for single parents regardless of the reason for their circumstance, the Maori marriage rate plummeted.

Welfare had a more devastating effect on Maori families because their incomes were lower and Maori men couldn’t compete with the DPB as easily. Pacific Island families have withstood the sole- parent- subsidisation assault better due to other cultural and Christian traditions which uphold and protect marriage and intact families. Even Pacific Island single mums are more likely to reside with their extended family.

But again, the welfare system didn’t discriminate against Maori and Pacific Island children. It sought to relieve their poverty by replacing incomes lost to unemployment or a missing partner. That it achieved the opposite – grew the incidence of relative poverty – is an appalling result.

Amnesty International makes pronouncements about every country in the world (in this particular report, 160 countries) but cannot intimately understand the development of child poverty locally. The only purpose this report serves is to provide headline fodder for the political Left.

Consequently this sort of claim soon has the silent majority’s eyes glazing over. It reads like a statement about minority rights in the 1930s or earlier. It doesn’t reflect the reality of New Zealand in 2015.