Singapore’s education system is relatively a small system, with about 450,000 school-going students educated in a system with roughly 369 schools staffed by a teaching workforce of around 33,000 teachers (Education Statistics Digest, 2015). A compact education system by world standards housed in a small country with a land areas of only 720 sq km and a population size of 5.5 million people (Department of Statistics, 2015.).

Using simple arithmetic, it is not difficult to surmise that the distribution of 450,000 students in 369 schools makes for rather large numbers of students in each school. This is indeed the case. With schools varying in student numbers, the average student population per school is about 1,200 students with some schools having student numbers totalling about 3000. All schools are considered as being urban within this tiny island, city state and the divide into rural versus urban schools as one would find in other larger systems, is not applicable to the Singapore context.

The Singapore government invests heavily in education and this is evidence by its spending on education. The budget devoted to education in the 2015 national budget is S$12.1 billion (Business Times, 2015), comprising 15.1% of its total budget and it is the second largest proportion of national budget spending behind just the amount allocated for Defence. Expenditure on education is regarded as an investment for the development of human capital since Singapore does not have any other natural resources apart from human resource. Human resource, as our only natural resource is thus precious, and needs to be developed for the purpose of nation building and long-term sustainability.

In 2015, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) ranked Singapore on top of the league tables of education systems around the world. This ranking is based on the students’ performance in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) internationally benchmarked test.

Table 1. Performance of Singapore students in PISA and TIMMS since 2007 (Source: MOE, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2013).

2007 2009 2011 2012

PISA

Mathematic Literacy Skills 562 (2nd) 573 (2nd)

Reading Literacy Skills 526 (5th) 542 (3rd)

Science Literacy Skills 542 (4th) 551 (3rd)

Computer Based Assessment

Creative Problem Solving 562 (1st)

Mathematics 566 (1st)

Reading 567 (1st)

TIMMS

Mathematics (S2) 593 (3rd) 611 (2nd)

Science (S2) 567 (1st) 590 (1st)

PISA Programme for International Student Assessment

TIMMS Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study

The key question asked by many educators and policy makers alike is, how did students in Singapore managed to perform well in both the PISA and Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS)? What are some possible success factors? To excel in these internationally benchmarked assessments, students have to demonstrate knowledge and additionally, they have to demonstrate the ability to apply their knowledge well to solve real-life problems. How did this happen? We believe that this is due to a combination of factors. This paper aims to highlight some of the key features of the Singapore Education System which might collectively explain the high performance of the students in these internationally benchmarked assessments.

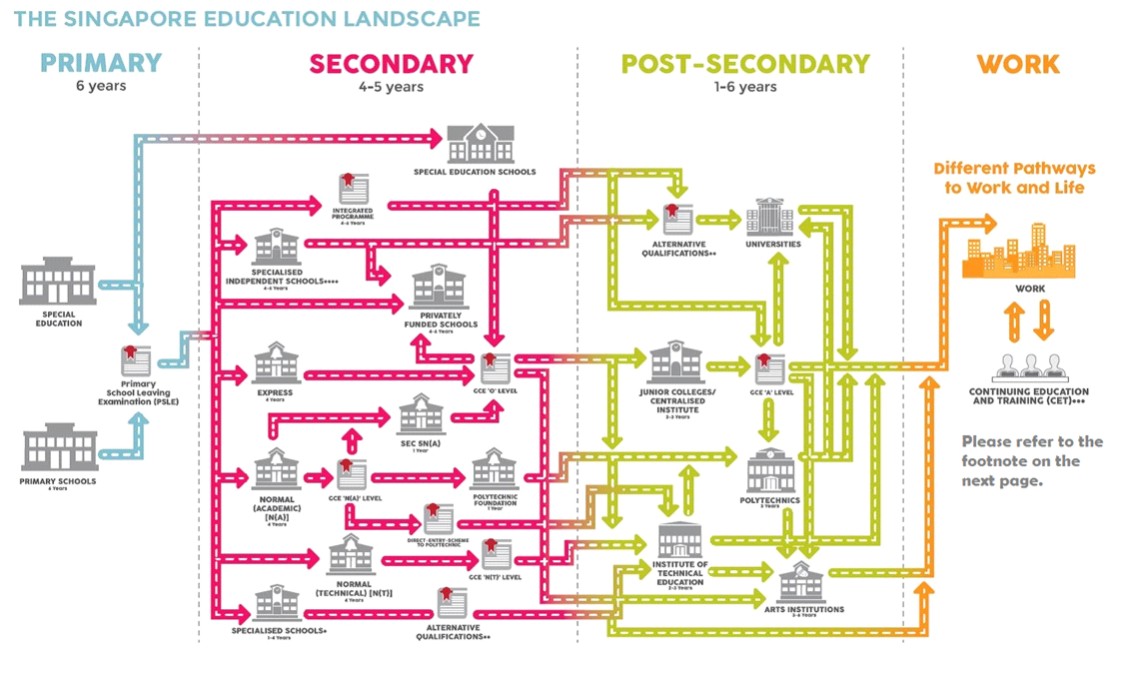

Many Pathways to Provide for Differentiated Learning

The Singapore Education system recognises that different students have different learning dispositions and preferences, and in response, it has provided several differentiated learning pathways to cater to the different learning profiles of students. The education pathways begin with 6 years of elementary school and 4 to 5 years of secondary school education. After 10 to 11 years of education, students can choose a vocational pathway through the Polytechnic route or the academic pathway through the Junior Colleges. Student on both the pathways can have an opportunity to pursue university education at the end of their study based on good academic results and career choices. Of the annual student cohort, some 30% will enter university, some 48% will pursue Polytechnic education while the remaining students will pursue technical education at the Institute of Technical Education (Education Statistics Digest 2015). Figure 1 illustrates the differentiated pathways open to students based on their academic or vocational interests and preferences.

The philosophy that underpins the Singapore Education System is that every student learns differently and each has different strengths. Hence for those who are academically-inclined, they will pursue the academic pathways whereas those who are more hands-on in their learning styles can engage in a pathway where more applied learning approaches can be adopted. Through such differentiated learning pathways, each student can progress at his/her own pace and gain confidence along their educational journey. The key goal is to ensure that every student will be adequately prepared with certain skills that will enable them to be employable and self-supporting in their life journeys. If this can be achieved systemically, then social issues such as those caused by unemployment, can be minimised.

It is also to be noted that irrespective of the pathways a student may choose to pursue, it is believed that foundational knowledge is essential for their progression. Thus, much effort is put into the teaching of Mathematics and Science to provide the necessary foundational knowledge, albeit at different levels. Different approaches are adopted for students in the different pathways to cater to their individual learning profiles. Furthermore, it is the pathways provided in the Singapore Education System can be described as one with bridges and ladders. This analogy is significant as it symbolises that there is no dead end regardless of which pathway a student may choose. A student may choose the vocational pathway, but if he/she can do well along that pathway, the opportunity to pursue a degree course in the university will be open. It is for this reason that it is important to provide a strong foundational knowledge to all students as we cannot predict where the student may land up in their educational journeys.

Fig 1. The Singapore Education Landscape (Source: MOE, 2015)

Footnote:

* Specialised Schools offer customised programmes for students who incline toward hands-on and practical learning. These schools include Northlight School, Assumption Pathway School, Crest Secondary School, and Spectra Secondary School

** Alternative Qualifications refer to qualifications not traditionally offered by the majority of mainstream schools in Singapore.

*** Continuing Education and Training (CET) is designed for adult learners or companies looking to upgrade the skills and knowledge of their employees.

**** Specialised Independent Schools offer specialised education catering to students with talents and strong interests in specific fields, such as the arts, sports, mathematics and science, and applied learning. These schools are the Schools of the Arts, Singapore Sports School, NUS High School of Mathematics and Science, and the School of Science and Technology.

A System That is Responsive to Landscape Changes

The Singapore Education System is a responsive system that takes serious consideration of both local and international landscape changes and proactively responds to them. The desired outcomes of education are to prepare our students to be relevant with the times and be able to contribute to the economic development of the country. In order to be relevant, the system has to be responsive and evidence is shown by the system undergoing 4 iterations since our independence in 1965 (Goh and Gopinathan, 2008). The four iterations since 1965 will be briefly described to illustrate how the system responds to changes proactively to ensure that it is always relevant with the times.

Survival-Driven Education (1965 to 1978)

When Singapore attained independence in 1965, the tiny island state encountered numerous challenges, both economic and social. The unemployment rate was high and the literacy rate was low. The goals of education during this period were to build in every student foundational knowledge of literacy and numeracy skills so that they each have a good opportunity of being employable. While this model worked well, the attrition rate was high. Out of 1000 pupils that entered the primary education, only 440 reached secondary four after 10 years (Goh and Gopinathan, 2008). By the late 1970s, due to its open economic policies that welcomed multinational companies to set up production facilities in Singapore, the demand for skilled workforce became pressing. Thus, every student that drops out of the education system is one potential manpower lost. The next phase of educational development was thus to reduce school attrition rates and to educate the population to meet the manpower needs in tandem with the economic development of the country.

Efficiency-Driven Education (1979 to 1997)

This phase of educational development is to build skilled manpower and reduce school attrition rates so as to support sustainable development of the country. An extensive study on the high attrition rates was conducted so that the problem could be adequately addressed. Findings from the study established that with a single pathway of schooling, many students could not cope with the national curriculum and dropped out of school as a result. A solution that was implemented in 1979 was to create three pathways for different profiles of students so that each student in their specific pathways would be better able to cope with the curricula. Slower progressing primary students were allowed up to 8 years to complete primary education as compared to the normal 6 years, while secondary school students can take up to 5 years compared to the normal 4 years to complete secondary education. This ‘New Education System’ as it was termed therefore allowed students to progress at a pace more suited to the academic abilities. Such a move indeed produced significant results in reducing attrition rates. By 1986, only 3772 students which represented less than 1% of the total school population below the age of 16, left school without having at least 10 years of education (Goh and Gopinathan, 2008). It is also during this phase of education that vocational education was highly emphasized to equip students with the necessary skills to support the many burgeoning industries in the country.

Ability-Driven Education (1997 to 2012)

By the mid-1990s, the world had entered a new economic era. The world economy shifted from an industry-based to a knowledge-based economy. In a knowledge-based economy, every ability of a child is an asset when it is utilised in a way that creates value. Therefore, the goals of education moved towards enabling every child to develop their individual talents, and every opportunity was provided for the child to demonstrate his/her creativity and innovative spirit. Higher order thinking skills were also very much emphasized.

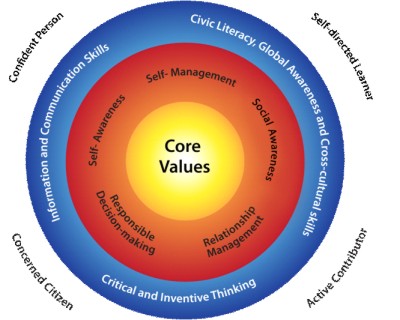

Student-Centric and Values-Based Education (2012-present)

The 21st century landscape is very much described as a VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous) environment. While the development of the potential of every child is important, it is envisaged that values and other attributes are extremely important and have to be inculcated in students so that they can confront the VUCA environment well. The focus in this phase is to develop four key education outcomes for the students, deemed to be important for this environment and they area) a confident person, b) a self-directed learner, c) an active contributor and d) a concerned citizen (MOE, n.d.). Educational programmes, pedagogical practices and assessment models were revised and aligned in order to build these attributes among the students.

A responsive education system requires a whole systemic reform when new iterations and initiatives are articulated. The changes are well and carefully communicated at all levels so that all programmes and activities are aligned. The outcomes are carefully monitored and measured so that where there are gaps, these will be bridged in order to achieve the desired end goals.

The system has very clear goals of education

In each educational phase, the Desired Outcomes of Education are very clearly identified and articulated. This is important because they provide a compass in guiding the development of national curricula, adoption of different pedagogies, refinements of assessments, professional development of teachers and the preparation of new teachers so that every component within the education system can be aligned to achieve these goals. This is the distinctive strength of the Singapore education system. Fig 2 illustrates the Desired Outcomes of the current Student-Centric and Values-Based Education phase. The four key desired outcomes namely a confident person, a self-directed learner, an active contributor and a concerned citizen are clearly identified. This leads us to the question as to what values and attributes can help develop the outcomes among the students. The educational goals are carefully articulated and implemented as they form the basis of how the national curricula as well as co-curricular activities are planned.

Fig 2. Desired Outcomes of Education (Source: http://www.moe.gov.sg/education/21cc)

The clarity of the Desired Outcomes of Education also facilitates the ease of communication to every educator in the system. This is another key strength of the system. In many education systems, there is a wide disconnect between the conceptualisation of policies and their implementation at the school level, and even more so, at the classroom level. If school leaders and teachers are not clear and are not fully informed of the philosophy and the Desired Outcomes of Education, then the programmes and educational activities planned for the students will not be coherent or aligned with the national goals of education. Perhaps Singapore’s education system is a rather compact one based on its small size such that the extent to which every educator is well communicated about both the philosophy and the principle on the importance of good communication must not be underestimated nor taken for granted. In larger education systems, a different model of impactful communication about the philosophy and Desired Outcomes of Education ought to be developed.

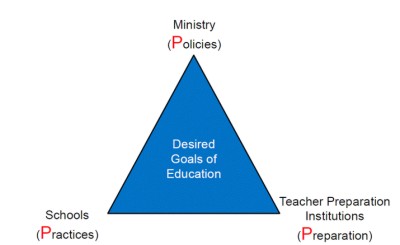

Alignment of Policies, Practices and Preparation

One of the key factors that contribute to the success of the Singapore Education system is that as a system, the key contributors to the attainment of the educational goals as a system, are well aligned. Fig 3 shows how the system works with the three key stakeholders to the education system namely, the Ministry of Education (MOE) which leads in policy development, the Schools that translate policies into practices and the National Institute of Education (NIE) which prepares all the teachers for the system, are aligned coherently to achieve the national Desired Outcomes of Education.

Fig 3. The PPP Model (Source: Lee & Low, 2014a)

We will further articulate the systemic coherence between the three key contributors to the education eco-system.

The MOE, being the main driver of the education system, will formulate and develop policies that will facilitate the achievement of the Desired Outcomes of Education. In the process of formulating and developing the major policies, it consults educational stakeholders widely for inputs and these include parents, teachers, school leaders, university academics, industry leaders who are employers and in many instances, the students’ views are also considered. Guided by the Desired Goals of Education, the policies cover curricular content (the Singapore Education system adopts a national curriculum), pedagogical practices and assessment models. In the spirit of the tripartite partnership, the Ministry would invite members from the schools and the national teacher education institute to provide their professional inputs in the reviews of these initiatives such as curricular or pedagogical reviews. This is not just to tap into the collective wisdom of the different contributors to the education system, but it also provides a platform where the three different partners can clearly understand the articulation of the policies that are shaped or formulated. Recognising that school leaders and teachers contribute a crucial role in the implementation of these policies, the Ministry also formulates and develops human resource policies that provide support for building up the professionalism of its educators. (MOE 2014) For example, one human resource policy that helps achieve this objective is to provide every teacher an entitlement of 100 hours per year for professional development and the cost of this professional development is either heavily or fully subsidised. The Ministry also develops resource allocation policies to guide the distribution of resources that – support the different enrichment programmes organised in the different schools for -students such that other attributes beyond academic goals can be developed among the students (MOE 2012). Singapore adopts a holistic education approach so that the Desired Outcomes of Education as shown in Fig 2 can be achieved system-wide.

The next group of contributors within the education system is the schools. Schools play a key role in helping students to acquire the Desired Outcomes of Education. School leaders and teachers must translate the policies of the MOE into the appropriate practices that will enable student learning such that they will acquire the Desired Outcomes of Education. School leaders must work with their teachers to identify areas of professional development for their teachers so that they will be equipped with the necessary professional competencies to be able to deliver the national curricula School leaders must also lead in creating the learning environment that will support the appropriate pedagogical practices to be adopted. This will include classroom reconfiguration as well as harnessing the learning environment outside of the classroom that would engage the students to learn in a manner best suited to their learning profiles. School leaders and teachers also plan and organise co-curricular activities beyond formal lessons so that students will be able to acquire the attributes beyond academic goals as envisioned under the holistic education philosophy.

The third group of contributors to the education system is the Teacher Educators who prepare teachers for the system. Because of the compact geographical make-up of the island city-state, Singapore has only one teacher education institute, unlike other countries where there are many teacher education providers. The National Institute of Education (NIE) is the sole teacher education institute in Singapore and has the responsibility of preparing every teacher and school leader for the education system. In the light of this unique circumstance, it is of paramount importance that the NIE must prepare Beginning Teachers with therelevant so that they can deliver the curricula and activities through appropriate approaches and practices that will enable the Desired Outcomes of Education to be achieved. The teacher preparation programmes must therefore take into consideration of the policies of the Ministry as well as the practices in schools so that there is overall systemic alignment. To facilitate this process of alignment, NIE works in close partnership with both the Ministry and the schools through various established committees and platforms. In reviewing and enhancing teacher education programmes in response to the changing 21st century landscape and which culminated in the development of the “Teacher Education Model for the 21st Century” close consultations with the schools and the Ministry were made. The Steering Committee that oversees that review process included several members from the schools as well as the Ministry so that their inputs can help align the educational goals across the system. Additionally, the Director of the National Institute of Education (functioning at the equivalent level as the chief academic and executive officer of the teacher education institute) has to attend the weekly meetings comprising members of senior management of the Ministry of Education chaired by the Minister of Education This arrangement and platform for coordination between key stakeholders in the Education system is an important one as any policy or issue that is discussed which has potential implications on teacher preparation will have an input from teacher educators as represented by the Director of NIE. Furthermore, if any policy is approved at the Ministry level, the information, in particular, the thinking behind the articulation of that particular policy will be looped rather immediately back into NIE for consideration for the refinement or enhancement of its teacher preparation programmes.

In a compact education system, the tripartite relationship and partnership is of great importance so that every contributor aims for the same goals and each has a very clear understanding of their respective roles. This Policy-Practice-Preparation (PPP) model can only be achieved when there is mutual respect and trust between every party within the partnership. Very often, policy makers tend to take the upper hand and impose their views more dominantly. Likewise, academics in the teacher preparation institution would consider themselves better informed because of the research they undertake or the information they gather from their international peers and might exhibit some form of academic arrogance. The school leaders and teachers may be of the view that they know best about what is happening at the ground level, meaning the actual situation in the classrooms hence may expect their views to be given greater emphasis. These difficulties can only be avoided or overcome when mutual respect exists within the partnership and that every view from any of the partners must be accorded equal importance and consideration. While policies are important in guiding the eventual actions taken, it is important that the policies must take into consideration the realities faced in the schools and policies must ultimately support and facilitate the professional roles of teachers rather than to cause any potential hindrance.

There are other factors that must also be considered in order for the PPP model to work well. Firstly, there must be an effective channel of communication so that policies are well disseminated and clearly explained. When a policy is ready for implementation, the Ministry normally arranges for several town hall sessions with school leaders at different levels as well as teachers in general. Such sessions provide not only a platform for the policy information to be disseminated, but also serve as avenues for clarifications and further refinements of the policy. Only when the teaching fraternity are clear about both the policy and the thinking behind it, will they be able to translate them into the most appropriate practices so as to achieve its intended outcomes. Likewise, when teacher educators are clear about policy formulation and the rationale behind it, will they then be able to translate and incorporate them into appropriate teacher education modules or activities. Secondly, there must be adequate devolution of autonomy to the schools and the teacher education institute. While the Singapore Education system can be described as a centralised system with the centre for decision making resting at the Ministry level, it is recognised that for effective implementation of policies, there must be adequate autonomy devolved to the institutional level. It is recognised that every school is different one from the other hence, the manner in which some of the policies are implemented must take into consideration the contextual circumstances surrounding each school. Regardless of the contextual circumstances faced by each school, they must always be guided by the Desired Outcomes of Education. This is why the Desired Outcomes of Education is so important to serve as a directional compass. With the devolution of autonomy to the schools, each school must be led by high quality school leaders. For this reason, the Ministry, in partnership with the National Institute of Education, has put in concerted efforts in building up a pool of highly competent and talented school leaders/principals. Thirdly, when the implementation of a particular policy requires resource support, the schools are given the support by the Ministry to organise the necessary enrichment programmes, undertake infrastructural improvements to enhance learning experiences or for the purpose of teacher professional development.

One might say that the PPP Model can only work well in a small and compact education system such as that of Singapore’s. It would be difficult to implement such a model in a large education system such as those found in large countries like the United States, United Kingdom for example. This may be true, but a large education system can be broken down into smaller geographical units and many principles of the PPP model could apply. For example, in the United States, it could be at the state or county level. The State of Delaware is a good example where elements of the PPP model will soon be visible in their implementation of their new Vision Coalition of Delaware: Student Success 2025 to elevate their education system in raising students’ learning attainment (Rodel Foundation of Delaware, 2015). It is indeed recognised that a successful education system cannot be teleported in totality from one locality to another, in particular when it crosses national and cultural boundaries. The key features of each system will have to be carefully analysed and adapted for adoption after considering the cultural and national contexts that will influence educational planning and development.

The Role of the National Institute of Education (NIE)

In many reports about high performing education systems that have been published, it is well recognised that good quality school leadership and teachers are crucial in enabling student learning (Chetty, Friedman & Rockoff, 2013; Darling-Hammond, 2000; Hattie, 2003). While good school leaders drive the transformation of the learning environment, and in empowering teachers to be innovative and creative as well as being nurturing to the students, it is the teachers who have the most intensive interaction in the classrooms and who would have the most extensive impact on student learning outcomes. How teachers interact with their students, the type of pedagogical practices that are adopted and the tools that they use to deliver their lessons, play crucial roles in the learning processes of the students. Hence, equipping teachers with the most appropriate competencies is therefore very important. This is well recognised by the Ministry of Education in Singapore which explains the heavy investment in the building up of a high quality teaching force, beginning with the pre-service phase and followed by extensive professional development initiatives.

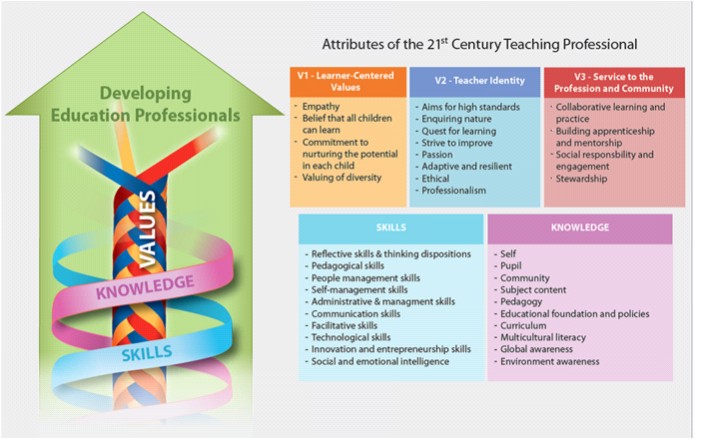

The contribution of the NIE is key towards the building of a high quality teaching force. As NIE is the sole teacher education institute that prepares all teachers for the education system, it is entrusted with the heavy responsibility to ensure that teachers graduating from the institute will be equipped with the appropriate attributes and competencies that will empower them to be relevant in the classrooms occupied by the 21st century digital learners. To ensure that this responsibility is fulfilled, NIE embraces a culture encapsulated by three descriptors namely, Responsiveness, Relevance and Rigour. It is through embracing this spirit, that NIE undertook an extensive review of its programmes to develop a new model for teacher education entitled “Teacher Education Model for the 21st Century” or TE21 for short (NIE, 2009).

Teacher Education Model for the 21st Century (TE21)

In the spirit of being responsive and relevant, NIE undertook an extensive review of our teacher education programmes in 2009.The institute recognised that globalisation and the increasing convergence of digital technologies were the defining characteristics of our world at the turn of the 21st century. Boundaries are also blurring as a result of the swiftness of information and knowledge transfer. Demands for new job skills due to technological advancements are also fast-evolving. In the classrooms, the profiles of our digital learners are also changing. Many educators dubbed our learners as EPIC learners, describing them as learners who like Experiential learning, keen to Participate in the process of learning, are very much Image-driven and they like to be Connected as a group in the process of learning either physically or virtually. Thus, given such a scenario, what kinds of attributes and competencies should teachers possess in order to be relevant in the classrooms? Furthermore, the classroom landscape is also growing in complexity due to the diversity of learners with different cultural and religious backgrounds as well as academic capabilities.

Driven by the external factors as outlined above and guided by the Desired Outcomes of Education an extensive teacher education programme review was conducted in 2009 to look at the design elements of a Teacher Education Model that would be relevant in meeting the demands of the changing local and global educational landscape.

The review produced a teacher education model that is very much anchored on Values, Skills and Knowledge as shown in Fig 4. It builds on the existing framework by enhancing the values framework to include 3 sets of values that firmly anchor the teacher as being a professional.

Fig 4. New Values, Skills and Knowledge (V3SK) Model (Source: NIE, 2012, p. 6)

The review took a futuristic perspective of preparing the 21st century teacher to support the 21st century learner. In the iteration of this teacher education model, the focus is on the child as the learner who must be at the centre of our teacher education mission. Our goal is to graduate a thinking teacher, one who is attuned to the needs of the child as a learner with respect to their individuality, personal development and diversity. We are also cognizant of the research evidence that teacher beliefs and expectations have a strong co-relation to the outcomes of learners (Tan & Liu, 2014; Day, Kington, Stobart, & Sammons, 2006; Gu & Day, 2007). Based on this setting, TE21 articulates the 3 sets of value paradigm as follows which is reproduced from the TE21 Report (NIE, 2009):

Value Paradigm 1 : Learner-Centred values

Empathy

Belief that all children can learn

Commitment to nurturing the potential in each child

Valuing of diversity

Believing that all children and youths can learn, a teacher’s first and foremost characterisation as a professional is putting his/her care for the learner at the centre of his/her work. Teacher education will emphasise awareness of the learner as an individual. This includes understanding the development, diversity and academic profiles of learners.

Value Paradigm 2 : Teacher Identity

Aims for high standards

Enquiring nature

Quest for learning

Strives to improve

Passion

Adaptive and resilient

Ethical

Professionalism

Teacher identity is an important characteristic that defines who a teacher is, truly a professional in the classroom. Teachers should be characterised by high standards and a drive to learn to be a better professional. The drive to learn is particularly important when one is charged with the responsibility of educating children in an era that is characterised by rapid and continuing change. As a professional, a teacher ought to use his special knowledge and skills appropriately in a variety of institutional contexts with diverse student demographics. He should understand the responsibilities that are entrusted to him in nurturing the learners under their charge and would engage in equipping themselves to discharge these responsibilities. . In a nutshell, teachers must be proud of their profession and will always strive to serve as professionals.

Value Paradigm 3 : Service to the Profession and Community

Collaborative learning and practice

Building apprenticeship and mentorship

Social responsibility and engagement

Stewardship

As professionals, every teacher must strive to contribute towards the building up of their profession and be proud of their profession. There must be a collective effort to achieve this goal. Teachers must be committed not just to their teaching profession but to the community as well. Teachers should always be looking to mentors and role models, and be prepared to mentor others at a later stage in their careers. Like the medical profession where senior doctors mentor junior doctors to build up the professionalism of the profession, teachers ought to follow suit. They should have a deep sense of responsibility to contribute to the future of the larger community.

The Skills and Knowledge Paradigm

The Skills paradigm drives the identification of the competencies that a Beginning Teacher ought to be equipped with upon graduation from the NIE. The list of skills that were identified to be important for a Beginning teacher in a 21st century classroom are,

Reflective skills and thinking dispositions

Pedagogical skills

People management skills

Administrative and management skills

Self- management skills

Communication skills

Facilitative skills

Technological skills

Innovation and Entrepreneurship skills

Social and emotional intelligence

NIE recognises that in the 21st century classroom where learners will take ownership of their own learning, teachers must have facilitative skills to encourage collaborative learning. These skills must be complemented with technological skills so that technological tools can be adopted to enhance learning in the process. To build confidence in students which is one of the four Desired Outcomes of Education, the development of such attributes through social and emotional learning is important hence teachers ought to develop their own social and emotional intelligence.

The knowledge paradigm provides the foundations that would empower the Beginning Teachers to apply their skills to nurture the learners in their process of learning. The areas of knowledge that are important to a Beginning Teacher are identified as follows,

Self

Learner profiles

Community

Subject content

Pedagogical Content Knowledge

Educational Foundation and Policies

Curriculum

Multicultural literacy

Global awareness

Environmental awareness

NIE believes that a professional teacher must attain mastery of the subject that he teaches, especially in today’s context where students can access knowledge from a wide range of sources. Only with a good knowledge of the subject can a teacher be able to help students to discern and facilitate the process of learning. It is also important to note that the teacher would in many instances co-learn with the students. In the 21st century landscape, teachers need to be aware of topics beyond the classrooms hence the need for global and environmental awareness, multicultural literacies and the knowledge of the community.

Theory-Practice Nexus

The theory –practice nexus has been a topic of long deliberation among teacher educators. Those teacher education programmes offered by universities are often criticised as being too theoretical and graduates may not have the confidence in managing a class upon graduation. Likewise, a practice-theory gap is likely to occur if teacher preparation focuses primarily on classroom practices. In the 21st century classroom where many complex issues are at play vis-a-viz differentiated learner profiles to the learning environment and the curricula, there is a need for a teacher who knows the why and the how of teaching, hence the importance of enhancing the theory-Practice nexus (Liu, Tan, & Hairon, 2014). NIE therefore emphasizes on equipping the student teacher with a strong theoretical foundation and being given adequate time in real classrooms to translate the theory into practice under the guidance and mentorship by both the NIE professor and the Senior Teachers in the schools. During the Practicum period (clinical field experience in schools), the student teacher is encouraged to reflect, learn through experiences, adopt different types of pedagogical tools where appropriate with due consideration given to learner profiles and to be involved in some form of action research that demands an enquiring mind. At the NIE, students teachers spend about 35-40% of their time in the schools for the Practicum. The NIE works closely with the school management to provide meaningful mentorship to nurture the student teacher. Every school in Singapore works in partnership with NIE in the preparation of the next generation of beginning teachers.

To encourage student teachers to practise purposeful reflection, they are encouraged to document their learning journeys in their e-portfolios. Their reflections, discussions with their mentors are recorded in their journal and these would be shared with fellow student teachers, a process that will help to build up learning communities among the teachers when they begin their work in t-schools (Tan & Liu, 2014). These e-portfolios will follow the student teachers when they graduate from the NIE and they can continue to document their learning journeys and build their professional teaching portfolios while teaching in schools.

Group Endeavours in Service Learning (GESL)

As the teacher preparation programmes at NIE are very much value-based, several of the values will be acquired through activities that take place beyond the classrooms rather than during formal curriculum time. Every student teacher is required to participate in a community involvement project known as the GESL project during their time at the NIE. Groups of 20 student teachers facilitated by a professor will each plan, design and implement a service learning project. Many groups will venture into providing humanitarian assistance to the elderly or the disadvantaged populations or they may choose to spend time teaching the English language to foreign workers in Singapore so as to help them to integrate into the society better for example. Through such activities, student teachers are able to acquire the values of service for the less fortunate and several other community-related values. With such experiences, they will be able to lead and organise service learning programmes for their pupils in the schools. The inculcation of such values in the schools among the pupils will hopefully help them develop to be active contributors to the society when they grow mature into adulthood.

The transformed learning environment

The learning environment of the 20th century is designed for passive learning where the teacher is the central focus of the classroom. However, in the 21st century where students will take ownership of their own learning and where 21st century skills are to be acquired, there is a need to transform the classrooms with a configuration where there is an active participation on the part of the students and where the role of the teachers is primarily that of a facilitator. To actualise such a learning environment for teaching and learning, NIE transformed its 72 tutorial rooms into collaborative class rooms as shown in Fig 5 to support the acquisition of 21st century skills (Lee & Low, 2014b).

Fig 5. New Collaborative Classroom

One may ask, how does the transformed collaborative classroom work? It adopts the Flipped Classroom Pedagogy concept where students are given prior learning materials to study before coming to the class. During face-to-face classroom sessions, students will be seated in small groups and facilities will empower them to use their technological tools. Each group may be give a case study or a specific scenario and the group will be required to focus on a certain aspect of discussion and at the end, make a presentation. Through this process of learning, students will be able to acquire a) collaborative skills – learning how to work with one another and taking on different roles within the group, b) interpersonal skills – learning to respect diversity of views and to converge on a consensus, c) higher order thinking skills through questioning and deliberation and also the synthesising of the answers and d) communication skills through giving presentations.

One might question NIE on this approach of equipping teachers with the 21st century skills in case the school environment has not evolved in tandem. The simple answer is that NIE must prepare the next generation of teachers to be change agents. NIE must prepare thinking teachers with skills that will enable them to bring about the changes to the learning environment in the schools so that the students will acquire the 21st century that would be relevant in the new landscape.

Parental Engagement

Every parent an Engaged Partner, this is the goal of the Ministry of Education (Heng, 2015). The Ministry recognises that in the education of a child, it is important that the parents are on board as an engaged partner, in particular where the inculcation of values is concerned. Parents can reinforce the values taught in the schools through their emphasis on values such as being resilient, honesty and integrity and, care and concern for the family, community and the nation (Heng, 2015). Such values are emphasised through public forums and media.

The interaction between schools and parents is currently achieved through two platforms. Firstly, each school has set up a Parent Support Group (PSG) comprising mainly of parent volunteers who serve as a bridge between the parents and the school. The PSG supports the school in activities and programmes (Hawazi, 2012). Parent volunteers provide support in supervising the students when they go for outings, especially for the primary school classes. The PSG will also help out in dealing with other parents that may have difficulties relating to their children’s studies or behaviour. Some of them who may have special expertise such as in computer literacy or in parenting skills may conduct classes for other parents and even teachers. Through such interaction with the schools, parents will be better informed of the schools’ goals and emphasis hence will reinforce various them at the home environment (Schoolbag, 2014). The second platform is the annual meeting between the teachers and the parents on a one to one basis to discuss the progress of their respective children (Schoolbag, 2015). Towards the end of the year, when the annual examinations are over and the report cards are completed, the class teacher will meet every parent of the students in the class. During this meeting, the teacher will report to the parent on the holistic performance of the child, both in terms of the child’s academic and social development. The teacher will describe to the parent the strengths and weaknesses of the child and how the school can work with the parent to address the concerns. Such a meeting is a true reflection of the partnership between the school and the parent and it also allows the school and parents to take a joint effort in the education of the child.

In order to establish a better interface between parents and the Ministry, the Ministry has also set up a national committee called COMPASS.

The National Advisory Council, COMPASS (COMmunity and PArents in Support of Schools) was established in December 1998 to advise the Ministry of Education on ways in which school-home-community collaboration could be strengthened and promoted. COMPASS is chaired by officials from the Ministry of Education and comprises members from the various stakeholders representing parents, self-help groups and the business community (MOE, 2014 COMPASS) aims to develop a common understanding among students, parents, schools and the community about the role that each group should play in a concerted effort to achieve the desired outcomes of education.

The role of COMPASS is to:

- Provide feedback on MOE policies and initiatives from parental perspectives;

- Actively reach out and encourage parents to partner schools to deliver student-centric values-driven education; and

- Promote school-home partnerships to achieve student centric values-driven education by leading and organizing parent outreach events, forums and discussions.

The Council meets quarterly for discussions on policies and programmes. Members also gather information on the challenges faced by schools involving parents and the community as well as how they are overcome, and how schools support the education of students (MOE, 2014).

In Singapore, parental support for the education of their children is strong. Parents pay strong attention to the education of their children and this further emphasises to students the importance of devoting their time and energies in schools.

Conclusion

We started this chapter by stating that the key question often asked is, what contributes to the high education attainment of students in Singapore. Ultimately, it is the collective influence of the factors outlined above interacting with each other that contribute much to the high level of educational attainment of Singaporean students. There is no one factor that can be said to wholly contribute to the high student learning outcomes but a combination of several factors taken together. It can be said that the Ministry has rightly identified the quality of both the school leaders and the teachers as being of key importance and they have rightly invested national resources to building up such a high quality teaching workforce. There are several education systems around the world that had invested in the infrastructures and equipment to ensure that they are cutting- edge, but with a poor quality teaching force, did not achieve high student achievement in education.

While the success factors cannot be teleported from one education system to another in view of difference in cultures and context, nevertheless, useful lessons can be learnt from the Singapore Education system. These factors can be contextualised before adoption so that they can work to enhance the quality of at the systemic level. Ultimately, much of Singapore’s educational success had its early beginnings post-independence, where the role of education and teachers were seen to be crucially tied to the important task of nation-building. Such a mantra still exists till today, and continues to guide Singapore’s education system as we aim to continually sustain and scale new peaks of excellence. Systemic coherence has been key to the nation’s educational success but moving forward, not resting on our laurels but continually striving to learn from good practices from other systems will ensure that we stay on top of the league.

Professor Sing-Kong LEE

Director (2006 – 2014)

National Institute of Education

Nanyang Technological University

Singapore

Associate Professor Ee-Ling LOW

Head, Strategic Planning & Academic Quality

National Institute of Education

Nanyang Technological University

Singapore

References

Business Times. (2015). Budget 2015: Key budget numbers. Retrieved from http://www.businesstimes.com.sg//infographics/singapore-budget-2015/key-budget-numbers

Chetty, R., Friedman, J., & Rockoff, J. (Sept. 2013). Measuring the impact of teachers II: Teacher value-added and student outcomes in adulthood. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w19424.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement: A review of state policy evidence. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8 (1). Retrieved from: http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v8n1.

Day, C., Kington, A., Stobart, G., & Sammons, P. (2006). The personal and professional selves of teachers: Stable and unstable identities. British Educational Research Journal, 32(4), 601-616.

Department of Statistics, Singapore. (n.d.). Latest Data. Retrieved December 2015 from: http://www.singstat.gov.sg/statistics/latest-data#14

Goh, C. B., & Gopinathan, S. (2008). The development of education in Singapore since 1965. In S. K. Lee, C. B. Goh, B. Fredriksen, & J. P. Tan (Eds.), Toward a better future; Education and training for economic development in Singapore since 1965 (pp. 12–38 ). Washington, DC: The World Bank

Gu, Q., & Day, C. (2007). Teachers resilience: A necessary condition for effectiveness. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(8), 1302-1316.

Hattie, J. (2003). Teachers make a difference: What is the research evidence? Retrieved from: https://www.det.nsw.edu.au/proflearn/docs/pdf/qt_hattie.pdf.

Hawazi Daipi. (2012). Speech, MOE FY 2012 Committee of Supply debate. Retreived from http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/speeches/2012/03/08/fy-2012-committee-of-supply-debate-sps-hawazi.php

Heng, S.K. (September 22, 2015). Keynote address, Ministry of Education work plan seminar. Retrieved from http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/speeches/2015/09/22/keynote-address-by-mr-heng-swee-keat-at-the-ministry-of-education-work-plan-seminar-2015.php.

Heng, S.K. (October 20, 2013). In Facebook. Retrieved from https://en-gb.facebook.com/MOEExCELFest/posts/622326384494004.

Lee, S. K. & Low, E. L. (2014a). Balancing between theory and practice: Singapore’s teacher education partnership model. InTuition 16, Spring 2014. Retrieved from: https://www.ifl.ac.uk/publications/in-tuition/intuition-16-spring-2014/opinion-balancing-between-theory-and-practice-singapore%E2%80%99s-teacher-education-partnership-mode.

Lee, S. K., & Low, E. L. (2014b). Conceptualising Teacher Preparation for Educational Innovation: Singapore’s Approach. In S. K. Lee, W. O. Lee & E. L. Low (Eds.), Levelling Up and Sustaining Educational Achievement (pp. 49-70). Singapore: Springer.

Liu, W. C., Tan, G. C. I., & Hairon, S. (2014). Developing teacher competency through practice in Singapore. In J. C. D. Mora & K. Wood (Eds.), Practical Knowledge in Teacher Education: Approaches to Teacher Internship Programs (pp. 109-126). Oxon; New York: Routledge.

Ministry of Education (MOE). (2015). Bringing Out The Best in Every Child. Retrieved from: http://moe.gov.sg/about/files/moe-corporate-brochure.pdf

Ministry of Education (MOE). (November, 2015). Education statistics digest 2015 Retrieved from: http://www.moe.gov.sg/education/education-statistics-digest/files/esd-2015.pdf

Ministry of Education (MOE). (2014). Growing our Teachers, Building our Nation. Retrieved from: http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/press/2014/09/growing-our-teachers-building-our-nation.php

Ministry of Education (MOE). (December 3, 2013). International OECD Study Shows That Singapore Students Are Ready to Thrive in the 21st Century. Retrieved from: http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/press/files/2013/12/annex-international-oecd-study-2013.pdf

Ministry of Education (MOE). (2012). MOE Keynote Address. Work Plan Seminar 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/speeches/2012/09/12/keynote-address-by-mr-heng-swee-keat-at-wps-2012.php

Ministry of Education (MOE). (December 11, 2012). International Studies Affirm Singapore Students’ Strengths in Reading, Mathematics & Science. Retrieved from: http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/press/files/2012/12/tp11-press-release-annex-b.pdf

Ministry of Education (MOE). (September 12, 2012). New Website for Parents and Resource Pack for Schools on Home-School-Community Partnership. Retrieved from http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/press/2012/09/new-website-for-parents-and-re.php.

Ministry of Education (MOE). (December 7, 2010). International OECD Study Affirms The High Quality of Singapore’s Education System. Retrieved from: http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/press/files/2010/annex-pisa-2010.pdf

Ministry of Education (MOE). (December 10, 2008). Singapore Performs Well Again in Latest Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) 2007. Retrieved from: http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/press/files/2008/12/timss-annex-a.pdf

Ministry of Education (MOE). (n.d.). Desired Outcomes of Education. Retrieved from: http://www.moe.gov.sg/education/desired-outcomes/

Ministry of Education (MOE). (2014). COMPASS. Retrieved from http://www.moe.gov.sg/compass/.

National Institute of Education. (2012). A Teacher Education Model for the 21st Century (TE21): NIE’s Journey from concept to realisation – An Implementation Report. Singapore: National Institute of Education. Retrieved from: https://www.nie.edu.sg/files/booklet_web.pdf.

National Institute of Education. (2009). TE21: A teacher education model for the 21st century. Singapore: National Institute of Education.

Rodel Foundation of Delaware. (2015). Vision Coalition of Delaware: Student Success 2025. Retrieved from: http://www.rodelfoundationde.org/resources/education-organizations/.

Schoolbag. (April 28, 2013). Parents and schools – partners in education. Retrieved from https://www.schoolbag.sg/story/parents-and-schools—partners-in-education#.VmkjEErRKko.

Schoolbag. (April 22, 2014). Parent volunteers share experiences and expertise. Retrieved from https://www.schoolbag.sg/story/parent-volunteers-share-experiences-and-expertise#.VmkjBUrRKko.

Schoolbag. (January 22, 2015). Every parent, a supportive partner. Retrieved from https://www.schoolbag.sg/story/every-parent-a-supportive-partner#.VmkjvkrRKko

Tan, O. S., & Liu, W. C. (2014). Developing effective teachers for the 21st century: A Singapore perspective. In O. S. Tan & W. C. Liu (Eds.), Teacher Effectiveness: Capacity Building in a Complex Learning Era (pp. 139-157). Singapore: Cengage Learning.