In a year or so, voters will be choosing their political party to become the next government.

One of the policy issues on the table is electricity. The Labour and Green parties have announced a policy to effectively nationalize privately and publicly owned companies by controlling their prices and their profits. NZ First proposes to reacquire the generation companies and create one large state-owned generator like the NZ Electricity Department (NZED) once was. They believe they can force down electricity prices, while at the same time guaranteeing security of electricity supply and encourage investment in electricity generation and distribution.

National, on the other hand, believes that the electricity sector works best within a competitive market, with a mix of private and public ownership, and regulation where there is no competition in those parts of the sector where there can be no competition i.e. the local lines companies and Transpower. This is the best way to get the lowest electricity prices consistent with guaranteeing security of supply and sector investment to meet increasing demand.

These are dramatically different approaches.

Furthermore, it seems that the National Government will proceed to partially privatize Meridian Energy now that the uncertainty over the Tiwai smelter’s future has been delayed for a few years. This follows the successful partial float of Mighty River Power.

National’s approach is followed by the rest of the world and gets security of electricity supply and the lowest power prices possible consistent with a long-term viable sector.

It is my view too, not from any ideological perspective, but simply from what achieves the best practical result for consumers: New Zealand’s energy history and experience in world energy markets shows that government owned or controlled energy companies cost consumers – or taxpayers where subsidies are paid – far more than an efficient competitive energy sector, with well designed regulation where it is necessary to make the markets work.

I first became involved in NZ’s electricity sector as a Treasury officer entrusted with overseeing the NZED in the 1970s, and then as minister of energy in the late 1990s. While there were good arguments for significant state involvement in building large power stations in the 1960s and 1970s, they did so only with high electricity prices. The arguments for monopoly government ownership became far less persuasive in the 1990s. By then the cost of energy and security of supply had become critical issues for household and business consumers in an open NZ economy that didn’t exist in the 1960-70s.

Labour, NZ First, and the Greens believe the only path to efficiency and lower power costs is through state ownership and control. Labour and NZ First are Johnny-come-lately joiners to the socialist policies promoted by the Greens. Labour supported competitive markets during the Fourth and Clark-led Labour Governments, and NZ First supported the move to competitive markets when it was part of the National-led coalition government in 1996-1999.

The country once had the sort of electricity policy mix the Lab-NZF-Greens are now promoting. Before1989, all power was generated and distributed nationally by the NZED (a government owned monopoly), and distributed locally by electricity supply authorities (ESAs, publicly owned local monopolies). Consumers had no choice of electricity supplier, and no options to get lower electricity prices.

To my knowledge, no other country is proposing re-nationalization of the electricity sector: moves are clearly in the other direction, to implement competition in electricity markets even in former centrally run economies such as Russia and China.

Some people in New Zealand believe that the electricity sector cannot be competitive, and prices will always be higher than in a state owned, politically determined industry. This belief is in spite of the fact that every other sector of the economy once owned by the government (e.g. telecommunications and airlines) is now operating in competitive markets, giving consumers choice and lower prices.

How many people would want the government to monopolize air travel or telecommunications again? Competition has produced palpable benefits for consumers, and has generated tax revenue for the government, whereas in the past taxpayers had been subsidizing these sectors.

Introducing competition into the electricity sector began in 1989 under the fourth Labour government. The reason why this change was pursued was simply because the state owned and controlled system was failing to deliver security of electricity supply, and prices had risen continuously at rates well above inflation.

Comprehensive changes were made in the sector. Local ESAs were encouraged to operate in a “business-like” manner, whereas many had been using their electricity consumers as cash cows to subsidize rates. National transmission was separated from the generation arm of NZED to increase transparency of pricing, but remained in state ownership – as it does today through Transpower.

The most comprehensive change was in the generation sector. NZED was spilt into competing generation companies, some owned by the private sector, but the majority – by generation capacity – remained in state ownership. A wholesale market was established where lowest cost electricity was supplied to consumers first.

What happened as a result of these changes?

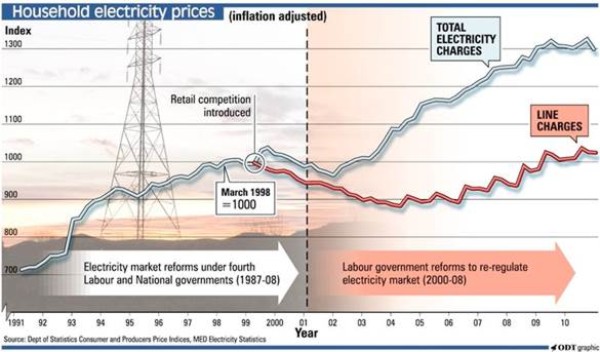

As the chart shows, when competition was introduced in 1998-99, real electricity prices fell on average for four years. This had not happened in the preceding 20-30 years of state ownership and control.

Prices fell more for some consumers than others: the commercial sector, and farming had been subsidizing households for years as prices were politically determined, with the result that very high non-household power prices helped make business and farming internationally uncompetitive.

Inflation adjusted prices for local lines distribution companies fell substantially for some years after 1999, as the regulator – the Commerce Commission – forced these monopoly companies to seek cost efficiencies and only allowed a reduced rate of return on capital because of the lower commercial risks they faced compared to competitive companies.

In 2002, the then Labour government began to re-regulate the market in a series of policy moves, although they didn’t move to change the structure of the market finally established in 1998 after a decade of reform.

The overall effect of these moves was to reduce the competitive pressures on the generators. Government policies reduced the ability of companies to build low cost thermal generation (such as low emission coal fired stations). There were other pressures as well that no government could avoid e.g. the ending of low cost gas supplies from the Maui gas-field, and the addition of increasingly expensive new generation capacity as lower cost alternatives were not available (such as wind power).

The result was a 72 percent increase in inflation adjusted power prices between 2002 and 2008. This had nothing to do with the structure of the market, but was principally the result of Labour’s policy mix where the market could not find the lowest cost generation capacity and the downward pressure on electricity prices of the 1998-99 reforms was eliminated by government policy.

During this time, the government also sought higher dividends from the state owned power companies, which in turn put upward pressure on prices.

After its election in 2008, National reinstated the policy pressures on competitive producers and retailers. Consumers were encouraged to shop around for alternative electricity suppliers, just as they do for air travel, mobile phones, or petrol, with initiatives like Powershop, the What’s My Number campaign and greater transparency of pricing.

As a result, power prices have risen at a far slower rate than in the 7 years prior to 2008. Whether they can or will fall further on a sustainable basis, depends on the policies being followed by the government of the day, and perhaps more importantly on the cost of each new increment of electricity generation capacity as New Zealand has run out of “cheap” renewable energy such as hydro.

There are some things to be done to make the market work better, and put pressure on the industry to deliver the lowest possible prices to consumers. I would include the following:

- Mandating smart meters into all electricity consumers’ premises

- Consider removing metering from the generators and putting them in the hands of independent meter operators or lines companies

- Improve the ability of independent retailers of electricity to provide electricity to household consumers, by removing any barriers to their ability to buy power from generators, independent retailers or the wholesale market

- Providing a power tariff for household consumers to buy power through the wholesale market (to get the benefit of low prices when the wholesale market is over-supplied)

- Make it easier for individuals to generate their own power and supply into the grid, with a certain, if necessary mandated, tariff payable by lines or generation companies

There are serious problems with the proposals of the Lab-NZF-Greens coalition. Most

countries that have tried the single power purchaser model at the heart of their policy have discarded them. Furthermore, the claims by the coalition that the big 4 electricity generators earned ‘super profits” of $4.3 billion has been firmly rejected by the author of the figure, Professor Frank Wolak1.

These are unforgiveable errors by the Lab-NZF-Greens, and significantly weaken the analysis underlying the justification for their policy, and therefore the policy proposals themselves. They would have been far better to build on the development of a world-best competitive electricity market in New Zealand, rather than U-turn to an electricity market model discredited in the rest of the world.

As a country we have clearly reached a fork in the road: do we continue to promote competitive measures to force competitive generators to look for lower cost solutions, together with sensible regulation on monopoly parts of the electricity sector; or do we return to the post-war model of monopoly state ownership and control, where political parties determine prices and profits?

- NBR 7 August 2013 ↩